Premium access: CIPD Festival of Work 2023 content on demand pass

Work. Autumn 2022, Issue 34

From auto parts and energy to grain and palm oil, the war in Ukraine has been disastrous for international supply chains. Does this herald a new era of near shoring and localisation?

By Andrew Saunders

Ironically enough, the history it apparently called time on has not been kind to the title of Francis Fukuyama’s influential 1992 bestseller, The End of History (or to give it its full monicker, The End of History and the Last Man). Even amid the heady excitement of those distant days, when the fall of the Berlin Wall, the rise of the EU and the implosion of the old Soviet Union seemed to herald a bright new era of international unity and borderless globalised trade, the argument that western liberal democracy had ‘won’ the battle of political ideas, once and for all, was provocative.

Thirty years later, after the financial crash, Brexit, the pandemic and the growth of nationalism, and now with nothing less than all-out war raging in Ukraine, western liberal democracy looks beleaguered rather than hegemonic, challenged on all sides by regimes ranging from the merely populist to the downright despotic.

Businesses of all kinds are discovering that barriers and borders can go up as well as come down, and that the consequences when they do can be painful. Thousands of companies, from professional services to pharmaceuticals and everything in between, have pulled out of Russia completely – including previously unstoppably-expansionist brands such as Coca-Cola and McDonald’s. Meanwhile, others are seeking alternative suppliers and customers closer to home.

The shock of seeing a country of 145 million people abruptly declared off limits even to those twin spearheads of international consumerism, a burger and a Coke, has highlighted concerns that globalisation – the ineluctable prime mover of the modern economy, the fabled ‘rising tide that floats all boats’ – might be stalling or, even worse, going into reverse.

Larry Fink – the boss of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset management company and a man who ought to know what he is talking about – certainly seems to think that an era is drawing to a close, and has made no bones about who he holds responsible. “The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put an end to the globalisation we have experienced over the past three decades,” he wrote in his letter to shareholders earlier this year. “It has left many communities feeling isolated and looking inward.”

Anecdotal evidence of glitches in the globalisation matrix is not hard to find. Queues of trucks forming at reinstated border crossings, and ships lying stranded at anchor outside clogged ports. Rising raw material prices and shortages of everything from steel and timber to microchips – the latter so severe that BMW, for example, has taken to shipping some cars without touchscreens to keep its production lines rolling. Meanwhile, one unnamed major industrial conglomerate has apparently resorted to buying up washing machines to strip out the chips for use in its own products.

No wonder that, in 2022, airy boardroom chatter about the unifying power of trade is in short supply. But while Fink may have a point, we should always be wary of the tendency for investment managers, however feted, to talk up their own books. And with $10trn on Blackrock’s books, there is a lot of talking to be done.

“The use of words like deglobalisation and nearshoring is peaking,” says ManMohan Sodhi, professor of operations and supply chain management at Bayes Business School. “These issues are certainly on CEOs’ minds, in terms of what they talk about in investor meetings and news conferences.” But words are cheap, he adds – they do not translate automatically into a slowdown in globalised trade: “Many newspapers are saying that globalisation is ending. But my interpretation of what Larry Fink was saying is that, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, globalisation must change, that it can no longer be what it was.”

Neither is it entirely fair to lay the blame for all of globalisation’s woes at the feet of the Russian bear, or even the pandemic. Other more prosaic factors are at work too – an earthquake in Japan and power shortages in Texas were both contributors to that aforementioned chip shortage, and energy prices were already rising before the Putin regime started to weaponise gas supplies to Europe through its control of the Nord Stream II pipeline. Rather, the current situation is a result, says Sodhi, of a sea change in companies’ awareness of, and attitude towards, risk. “Risk has been growing for a couple of decades and it has nothing to do with the invasion of Ukraine or the west’s proxy war on Russia,” he says. Whether that is major systemic risks like those arising from climate change, or apparently minor incidents with expensive consequences, such as the blocking of the Suez canal by container ship the Ever Given in March last year (which carried fruit and vegetables, laptops and Ikea furniture and whose grounding paralysed some $9.6bn of daily international trade for six days), the perception among business leaders and investors alike is that the world is becoming a riskier place to do business. “Whether you’re talking about commodities, the Dow Jones or the FTSE 100, risk is going up however you measure it.”

Then there are the ongoing tensions between China and the US. The world’s two largest economies seem increasingly anxious to escape from the lucrative but politically tricky co-dependency that has grown between them over the past few decades – even if doing so means damaging their own immediate interests. The US economy has shrunk in both quarters of the year so far, and the decades-long Chinese export boom that has driven its unprecedented expansion and underpinned so much of globalisation shows signs of drawing to a close.

“Risk has been growing for decades and it has nothing to do with the invasion of Ukraine or the west’s proxy war on Russia”

In April, overseas shipments from the country that has become the high-tech workshop of the world were up a mere 3.9 per cent year-on-year in dollar terms. So what is painted as a decline or even reversal in globalisation may be more of a pragmatic response to a new reality in which politics is at least as important as economics. This is what US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen has described as ‘friendshoring’ – blocs of politically aligned nations that will tend to trade more with fellow members of the same club than with nations aligned to another bloc. Penalties for trading outside your bloc and preferential treatment for staying within it may also apply, of course. “The world is fragmenting; the reality is now about creating spheres of influence,” says Sodhi. But a fragmented world doesn’t necessarily mean less trade. “If America wants to broaden its sphere of influence by buying more from the Philippines and less from other countries, for example, that doesn’t reduce the number of tonne miles of freight in the world.”

This is globalisation 2.0, a world of intra-regional rather than truly international commerce. According to the UN, global trade in 2021 totalled $28.5trn, up 13.1 per cent on pre-pandemic levels. But this rise was driven by increases in regional rather than global trade. Intraregional trade in the Asia-Pacific region grew by 31 per cent in the first three-quarters of last year, while trade between the US, Canada and Mexico rose by 30 per cent to $1.3trn between 2016 and 2021. And not everyone has ceased doing business with Russia – 141 countries voted in favour of the March UN resolution demanding immediate withdrawal of Russian forces from Ukraine, but 35 countries did not. Trade between Russia and the rest of the BRICs, the loose alliance of developing economies first identified by Jim O’Neill in the noughties, grew by 38 per cent to $45bn between January and March 2022.

China has also signalled its intent to decouple from the west, setting up an international Yuan payments system to rival the Swift network – it is tiny by comparison but could grow quickly, as the US sanctions against Russia have made many smaller countries nervous of relying on the dollar. To those with memories long enough to recall the east-west stand off of the Cold War era, it seems like we have been here before, and that history, far from being ended, is very much alive and kicking us where it hurts. But to be fair to Fukuyama, his book is rather more measured than its title, and he did warn of the emergence of a Putin-like figure who could “drag us back into history”. It also captures something of the daring intellectual optimism of the time, in which consensus politics and growing trade links would both supercharge economic growth and cement peace and global political freedom.

“After the fall of the Berlin Wall, it did feel a bit like the end of history and that we would all be living in a world of free liberal democracies,” says Peter Cheese, chief executive of the CIPD. As a consultant with Accenture in the 90s and noughties, Cheese had a ringside seat from which to observe the rise of globalisation over that period. “Globalisation opened up the world, broadly speaking. It was about much freer movement of goods and services, and being able to go to almost any country and access talent.”

It was all a huge experiment in Ricardo’s classic economic theory of comparative advantage – that each country should play to its inherent strengths, with free trade enabling them to buy in everything else from abroad – and for quite a time it seemed to be working. Between 1980 and 2014, the share of global GDP attributable to international trade rose from 37 per cent to 57 per cent, according to the World Bank. In 2000 just four per cent of China’s urban population was considered middle class, for example, but by 2018 that figure had risen to more than 30 per cent. As Douglas Irwin of Dartmouth College, author of Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy, has noted, it is largely down to globalisation that almost all countries got richer in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, while global inequality and extreme poverty both plummeted in the same period. But then in the second decade of the 21st century – before either the pandemic or the invasion of Ukraine – the mood had shifted, says Cheese, and that sense of all-pervading optimism started to fade: “It felt like someone had put the handbrake on globalisation, and that free and open just wasn’t what everybody wanted anymore.”

If everyone was getting richer and more prosperous, what on earth went wrong? For one thing, globalisation was blamed for the creation of a sort of rootless economic elite who travelled everywhere but belonged nowhere. At best such people were viewed by the less-gilded masses as checking out of the notion of social responsibility. At worst, as envisioned by Malcolm Bradbury in his 1992 novel Dr Criminale, their lack of connection to any country or community could result in a life of self-serving moral ambiguity, even crime. But globalisation’s fundamental flaw was that the core ‘rising tide’ promise was proving less than entirely watertight. The unhappy truth was that some boats floated further and faster than others. The numbers of middle class people may have been rising in countries such as China and India, but they were simultaneously falling in the US and Europe as traditional labourintensive occupations shifted from west to east. So while the impact on the headline GDP of many countries has been positive, the distribution of that greater wealth has not, says consultant and former plc finance director Alastair Dryburgh: “The most significant consequences of globalisation are social – the more you move towards a frictionless global market, the more you move towards a situation where there are fewer and fewer winners, winning bigger and bigger, and more and more losers.”

Phrases such as ‘the squeezed middle’ and ‘the precariat’ are more than arresting headlines. In real terms, average wages in the UK are still below their pre-2008 crash levels. By contrast, the number of billionaires globally has boomed – up from just over 1,000 in 2010 to more than 2,700 in 2021. And is it just a coincidence that the rise of super-efficient giant globalised multinationals such as Amazon, Facebook and Google has been mirrored by the demise of thousands of jobs in traditional sectors like manufacturing and retail? These footloose tech giants can be seen as the ultimate expression of globalisation for both good and ill. We can buy stuff that 30 years ago we did not know we even wanted from all over the globe and have it delivered in a few clicks. And we can comparison shop for the best price on anything from a laptop to loose-leaf tea from the comfort of our own homes. But in doing so we have funded the creation of huge supranational corporations that often pay minimal taxes, and wield resources many governments would envy in pursuit of their own divisive commercial agendas.

No wonder there is a sense that the many are being left behind for the benefit of the few. If a decline in globalisation results in a more equal relationship between capital and labour, it might well be a price worth paying, Dryburgh reckons. “If the power balance in this country were to swing away from capital and towards labour, I think that would be enormously beneficial to the quality of life, even if you are someone who is already on the ‘right’ side of the divide.

“If you think about all the people we need to make this country habitable, like bus drivers, street sweepers and shop assistants, society would miss them much more than it would miss many of its more well-off members. If they can’t maintain a decent standard of living then something is very wrong.” Many firms are already feeling something akin to this via the tight labour market. Competition for talent is fierce and candidates can pick and choose the best jobs, and highest salaries.

This neglect of the local and everyday in favour of the global and glamorous has been thrown into stark relief by Covid. Locked-down communities across the world were forced to re-engage with their immediate neighbourhoods and many found the experience surprisingly positive. Local businesses employing local people that can tell a local story about the provenance of what they have thrived – a shift in consumer psychology that could have profound effects on business if it proves to be persistent.

Globalisation has also encouraged large companies to pursue efficiency over resilience in a way that has made them much more vulnerable to the kind of systemic shocks that are now stacking up, Dryburgh concludes: “What globalisation has mostly done in economic terms is trade off reduced costs against increased risk – swapping greater efficiency for lower resilience and increasing the chances of there being a single point of catastrophic failure.”

So there is a growing realisation that putting all your eggs in one basket may no longer be the smartest thing to do – intricate supply chains that rely on precisely timed deliveries from all over the globe are being replaced by stouter, less risky systems with redundancy built in so that, in the event of delays or shortages, Just In Time is less likely to become Just Too Late. “Firms are realising that there is a limit to how much they can rely on outside [overseas] production,” says Oded Koenigsberg, professor of marketing and deputy dean at London Business School. “They are investing in localisation, and that means we will see more British companies producing in Britain and more EU companies producing in the EU, for example.”

Critics have labelled Yellen’s idea of friendshoring as a cuddly 21st century name for old-fashioned and damaging protectionism. But a new era of trading bloc commerce might not be an entirely bad thing for some – it could play to the strengths of the EU, for example, which was after all originally conceived in the 1950s as just such a trading bloc. “The EU potentially has a huge advantage,” says Koenigsberg. “It is expensive to manufacture in Europe but the technical capability is all here: there are more manufacturing companies in the EU than there are in the US and they are more advanced than those in the Soviet bloc.”

Sodhi also reckons that the impact could be positive by some measures, as corporations hedge their supply chain bets. “Say I am a business buying clothes from China, and I decide not to buy from China anymore – because of their human rights record, or because my government now says that China is a strategic rival. Instead I might buy some clothing from Vietnam, some from India and a little bit from Bangladesh. Now I am buying from three countries, whereas before I was only buying from one.”

So what appears on the face of it to be a dead-end street for globalisation could yet turn out to have hidden turnings that lead to some unexpected destinations. The world may be dividing once again on what looks like uncomfortably familiar lines, but the outcomes of that shift remain unclear and businesses thrive by recognising that every cloud has a silver lining. Just as history didn’t end in 1992, we cannot be sure it will repeat itself now

In March 2021, the Suez Canal became blocked for six days after the grounding of Ever Given, a 20,000 TEU container ship. At least 369 ships were stuck queuing behind it, at an estimated cost of $9.6bn in lost trade each day

In March 2021, the Suez Canal became blocked for six days after the grounding of Ever Given, a 20,000 TEU container ship. At least 369 ships were stuck queuing behind it, at an estimated cost of $9.6bn in lost trade each day

Thousands of protesters march through central London in June as part of a cost of living crisis protest, organised by the TUC. Analysis by the union has found energy bills in 2023 could cost more than two months of average take-home pay

Thousands of protesters march through central London in June as part of a cost of living crisis protest, organised by the TUC. Analysis by the union has found energy bills in 2023 could cost more than two months of average take-home pay

Coca-Cola being advertised to the fishing communities of Jamestown, the oldest district of Accra, Ghana. Cuba and North Korea are the only two countries where this ultimate poster child for globalisation (and capitalism) cannot be bought or sold – at least not officially...

Coca-Cola being advertised to the fishing communities of Jamestown, the oldest district of Accra, Ghana. Cuba and North Korea are the only two countries where this ultimate poster child for globalisation (and capitalism) cannot be bought or sold – at least not officially...

Global Takeover

On top of the TV set, next to the obligatory photo of Albania’s communist dictator ‘Uncle’ Enver Hoxha, the Ypi family proudly displayed a Coke can. They had never tried the soft drink – even in the early 1990s, the price was equivalent to an hour and a half’s wages in this Stalinist enclave. But, as their daughter Lea Ypi observed in her 2021 memoir Free, discarded Coke cans became highly prized “markers of social status” for families like hers. Indeed, when theirs disappeared and their neighbours coincidentally acquired one, it caused a bitter, if brief, feud between the families. As an American icon, the Coke can has proved as potent as Elvis Presley and the Hollywood sign.

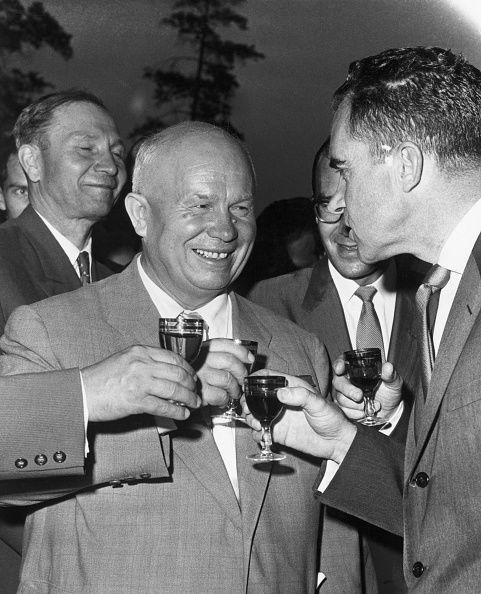

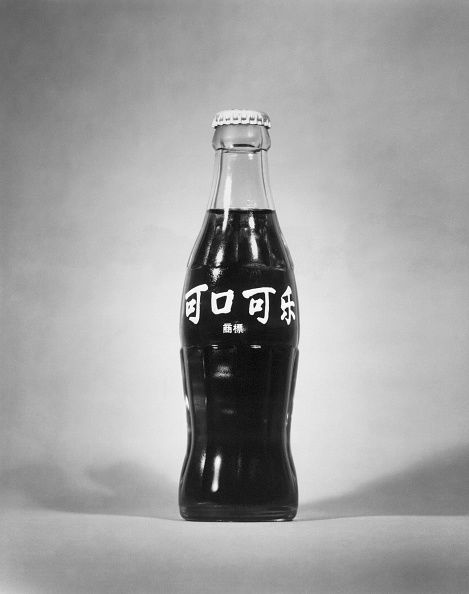

In Hoxha’s Albania, one of the poorest, most isolated countries behind the Iron Curtain, possessing one was a form of self-expression because houses and flats were painted the same colours. Simultaneously at odds with China, the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and the west, Hoxha’s regime wasted little time or resources on interior decor or soft drinks: thirsty consumers had to slurp a cheap Coke substitute made in Greece. The Coca-Cola Corporation, however, became the first major foreign investor in post-communist Albania in 1994, opening a bottling plant. In the former Soviet Union, Pepsi achieved a similarly iconic status after general secretary Nikita Khrushchev was photographed drinking it on a tour of America in 1959. After 14 years of diplomacy, Pepsi negotiated an exclusive deal with the USSR, locking out its rival for more than a decade. Stung by Pepsi’s coup, Coke wooed China. Things didn’t look promising at first – chairman Mao Zedong had once denounced the drink as a ‘bourgeois concoction’ – but in 1979, three years after his death, Coke returned to China after 30 years. In the early 70s, Coke’s ambition to ‘refresh the world’ inspired the global success of the ‘It’s The Real Thing’ TV ad, featuring the chart topping song ‘I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing’, the ultimate soft sell of globalisation as a heartwarming force for progress. In the words of brand consultant Giles Pearman: “That advert told a story that, just by buying a Coke, you could join a global family united by the hope of a better, more peaceful future.

Enver Hoxha was leader of Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985. His government outlawed travelling abroad and declared an atheist state

Enver Hoxha was leader of Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985. His government outlawed travelling abroad and declared an atheist state

Poverty stricken rural Northern Albania, in 1991. Albania's economyhas gradually improved following the fall of its Communist government the same year

Poverty stricken rural Northern Albania, in 1991. Albania's economyhas gradually improved following the fall of its Communist government the same year

Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and US vice-president Richard Nixon at the free Pepsi stand in the American National Exhibition at Sokolniki Park in 1959

Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and US vice-president Richard Nixon at the free Pepsi stand in the American National Exhibition at Sokolniki Park in 1959

In 1978 The Coca-Cola Company announced it would begin selling in China, becoming one of the first US companies to sell here in almost thirty years

In 1978 The Coca-Cola Company announced it would begin selling in China, becoming one of the first US companies to sell here in almost thirty years

Read more

Image credits

Maxym Marusenko/NurPhoto/Getty Images

Maxar Technologies/DigitalGlobe/Getty Images

Martin Pope/Getty Images

In Pictures Ltd./Corbis via Getty Images

Bettman/ Getty Images

Tom Stoddart Archive/ Getty Images

AFP/Getty Images