Premium access: CIPD Festival of Work 2023 content on demand pass

Work. Winter 2022, Issue 35

How many golf balls can you fit in a school bus?

While brain teaser job interview questions are thankfully no longer in vogue, the whole process is still loathed by many. So why do we still do it to ourselves and should we stop?

By Andrew Saunders

“Death will be a great relief. No more interviews.” Katharine Hepburn – the late, great Oscar-winning star of such classic movies as The African Queen and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? – may have been alluding to what we now call media intrusion into her private life when she made this typically salty remark, but for many in the world of work the sentiment resonates equally for that other, less glamorous but equally onerous, kind of ritualised interrogation: the job interview.

In a perfect world, job interviews would be a process of mutual discovery where employer and candidate establish whether their respective attributes amount to a good match. But in oh-so imperfect reality they can morph into a form of non-violent recruitment-based single combat – a battle that can only be won or lost. For too many candidates (and plenty of interviewers), whatever the official outcome, a job interview is something unpleasant and unavoidable that simply has to be endured, rather like exams or a trip to the dentist.

“Many of the students here see them [job interviews] as a kind of assessment that they just have to get through, where they will either be found to be OK or found wanting,” says Zoe McLoughlin, executive director of the Career Centre at London Business School, part of whose job it is to help MBA students find gainful and remunerative employment with organisations ranging from banks and consultants to high-tech start-ups once their studies are complete. They are a naturally competitive bunch, she adds. “People can take the results very personally, and feel rejected.”

But rather than seeing interviews as a zero-sum game of success or failure, McLoughlin counsels a more nuanced view of the outcome. “We’ll often say to students, if you didn’t make it through the interview then it’s probably a good indicator that you wouldn’t enjoy the job.” Because the aim of a well set up job interview – or even a series of interviews – should be to find the best candidate for the role, not only in terms of skills and ability but also that rather more human but also more elusive quality: fit. “It’s about selection and connection – a bit like dating,” she says.

It is not only candidates who can struggle with the interview process. Employers and interviewers do not always align what they hope to achieve with how they try to achieve it. The benefits of more diverse teams, for example, are now well understood, with a solid body of research demonstrating that diversity leads to better quality decision making and to a more representative and relatable working environment. But many firms that wish to seek more diverse candidates still rely on the selection process they have always used, only to wonder why they keep attracting the same type of applicants as they always have. Recruitment insanity, as Albert Einstein might have put it if he had started out in HR rather than the Swiss patent office, is repeating the same interview mistakes again and again and expecting different results.

“Job interviews are a really important part of the recruitment process but we give them the least thought”

The problem is at least partly one of ubiquity. Most people who recruit were themselves recruited via interview, so the interview itself has become part of the workplace furniture. In the same way that people use Microsoft Excel for all sorts of things it was not designed for, simply because it is already on their desktops, job interviews are familiar and fall readily to hand even if they are not always the best tool for the task. “What’s interesting about job interviews is that they are a really important part of the recruitment process, but they are also one of the parts of that process that has the least amount of thought given to it,” says Robert Newry, founder of behaviour-based HR tech firm Arctic Shores.

“If you think about how important interviews are, and how little time we put in to equipping and training the people who will conduct them compared to everything else we do around learning and development and performance management, for example, it’s really quite extraordinary.”

And while it has been axiomatic for decades in the HR world that structured interviews – those that follow a repeatable format, asking all candidates the same questions, and questions that are not generic but based on the specific requirements of the role concerned – are much more effective than unstructured ones, word it seems is still not getting out. “A structured interview that has been given careful thought and that is related to the role is, alongside cognitive ability, the best measure of whether someone is going to be a good hire or not,” says Newry. “Unstructured interviews are only marginally better than flipping a coin. And yet the majority of job interviews are still unstructured.” Perhaps because, however fatally flawed, they are easy, quick and cheap to conduct, especially for the armies of overworked line managers out there struggling to fill vacancies in a hurry while still having to keep on top of their own jobs.

Even those interviewers who claim to be conducting structured interviews may be fooling themselves, adds Newry. “People say ‘my interviews are structured; I go through the candidate’s CV and ask questions about their experience’. But that’s a complete waste of time too – that’s just using the CV as a comfort blanket to hide the fact that you haven’t properly thought through the questions you should ask.” So down on CVs is Newry that he thinks they should be done away with altogether, because they focus on experience rather than potential and lead to the exclusion of many desirable candidates. “We need to move beyond the comfort blanket. It’s not that experience doesn’t count, but a question of how we look at someone’s experience and decide if it is relevant to a job or not. We have to start interviewing people because they have the capability – to sift people in instead of sifting them out.”

The same unquestioned familiarity means that effectiveness often goes unchallenged too – even in today’s deteriorating economic climate where companies pore over the impact of every pound they spend in marketing and RnD, for example, the cost effectiveness of interviews is rarely considered. “Our resourcing and talent planning survey [in partnership with Omni RMS] found that there is very little evaluation of recruitment processes, either in terms of whether organisations are getting more diverse candidates, or even the return on investment of recruiting someone. Very few organisations are collecting that kind of data,” says Claire McCartney, senior policy adviser for resourcing and inclusion at the CIPD.

"Unstructured interviews are only marginally better than flipping a coin"

New CIPD guidance on inclusive recruitment, and a hiring guide for line managers, aims to address some of these issues and help create a more level playing field for marginalised groups, she adds. Like many things that seem to have been around forever and are rarely questioned, the origins of the interview are hard to pin down. But it is safe to say that conversations between candidates and employers have been going on in one form or another for a long time: writing in the FT some years ago, columnist Lucy Kellaway even claimed to have found a job interview question in the bible, in the shape of Jesus pithily asking would-be disciples: ‘What do you seek?’ Today’s interviewers, she added, “make much heavier weather of it”. In the pre-industrial world, however, landing a decent job was largely a question of patronage rather than competence. If your master was a prince or an aristocrat on the rise, then you could expect to rise with them. Conversely, no amount of talent could compensate for the lack of an influential sponsor. Come the industrial revolution and, while demand for labour exploded, capital still held most of the cards – into the early 20th century it was still common to see workers queueing outside factory and shipyard gates in the hopes of getting a few days’ or hours’ employment, more or less at the whim of the supervisor. Meanwhile, skilled work often ran in families (Nottinghamshire’s Victorian lacemakers, for example) obviating the need for firms to try very hard when it came to sourcing and selecting productive workers.

“Interviews are a brilliant chance to be face to face with someone, but they are also laden with bias and can be quite risky”

But mass state education and the rise of what would eventually become known as knowledge workers called for a method of selection that focused more on brainpower than muscle. US polymath Thomas Edison, apparently not content with holding more than 1,000 patents and being one of the founders of General Electric, is often cited as the inventor of the job interview as well as the phonograph and light bulb. But he may not entirely deserve the credit, because what he actually came up with was an early form of pre-employment selection test. The Edison Test, as it became known, comprised 146 remarkably diverse – one might even say arbitrary – questions, including the location of the River Volga, the proper ingredients of white paint and how Cleopatra met her end. It may sound like a high-stakes game of Trivial Pursuit, but Edison claimed that many mathematicians and scientists who applied for jobs with him lacked the breadth of knowledge he required of employees.

The founders of Google seem to have taken a leaf out of his book many decades later – back in the noughties when it was still a tech darling with the motto ‘Don’t be evil’, Google was famous for brain teaser interview questions such as ‘How many golf balls can you fit in a school bus?’, ‘Design an evacuation plan for San Francisco’ and ‘Why are manhole covers round?’ But the firm has since ditched both the slogan and the wacky questions, the latter as part of a drive to address – who would have guessed it? – an overly homogenous workforce dominated by too many Ivy League PhDs.

The issues with ‘clever’ interview questions are manifold. First, there is the risk that they are irrelevant to the job. Second, they are likely to favour certain personality types (extroverts over introverts, for example). Third, there is the ‘arms race’ issue – the interviewer may have read the latest edition of 100 Great Interview Questions, but what if the candidate has also read 100 Great Answers to Great Interview Questions?

“Interviews are the go-to method of assessing someone, and in a way they are a brilliant opportunity to be face to face with someone. But they are also laden with bias and can be quite risky – they can tip over into a bit of a tick-box exercise,” says Celine Floyd, chartered psychologist and director of talent practice at assessment specialist Cappfinity. The quality of too many interviews, she says, relies on the skill of the interviewer, and that can be little more than pot luck if they are not adequately trained or prepared. “It puts a lot of pressure on someone whose day job is being a lawyer, for example, to expect them to be able to spend an hour with someone and come away being able to say whether they will be good in the role, or a good fit for the organisation. That’s when the interview can become more of a question of: ‘Do I like this person?’” And not only is liking someone a bad predictor of performance, it is also a recipe for hiring more people who are like the ones you already have. “You are more inclined to like people if they mirror your background and your style of working. That’s a huge barrier to diversity.”

Even some attempts to make the job interview more objective have ended up having the opposite effect, Floyd adds. “My biggest peeve is the competency based interview, where the questions are things like: ‘Tell me about a time when you have led a team.’ They are based on the premise that past experience is predictive of future performance, which is hugely restrictive to people with different socioeconomic backgrounds, for example.” Competency-based interviews led to the catch 22 trotted out by many graduates of a certain age when asked by their parents when they were going to get a proper job: that however well qualified you may be, you cannot get a job without experience, and you cannot get experience without a job. Floyd reckons that the solution – or at least part of it – lies in interviewing for strengths rather than competencies. “Our philosophy is to look at what people enjoy and where they get their energy from, as well as what they can do. It’s not enough to look at someone’s competency. You have to look at their engagement and motivation too.” Done well, she claims that interviewing for strengths can lead to better candidate/role matching, improved wellbeing and lower absenteeism.

“It’s not enough to look at someone’s competency. You have to look at their engagement and motivation as well”

But for all the issues around interviewing, there are not very many companies that have abandoned interviews entirely. One example is Suma, the wholefoods co-operative, which prefers to use work experience sessions to select candidates for some jobs, but for the vast majority interviews still play an important role. However, it is increasingly common for interviews to take place in less formal environments, for example, and for candidates to be given at least some of the questions they will face in advance in an attempt to make interviews less pressured and intimidating.

“The purpose of the interview is for the candidate and the hiring manager to meet. It’s a two-way process that ultimately helps us identify people who will be successful and thrive in our organisation,” says Vicky Gallagher Brown, director of HR at Deloitte. Interviews also help avoid hiring mistakes, she says, and crucially support – and are supported by – other assessment tools. In common with many professional services firms, Deloitte is hiring more school leavers in an effort to improve diversity and to tap into new sources of talent in a tight market. It is a substantial and important undertaking – the firm has hired some 2,000 of these early career joiners this year and expects 3,000 more to join in 2023. Interviews for early joiners are augmented by a whole range of other assessments, starting with online maths and English tests and progressing to group work and job simulation sessions, where candidates tackle the kind of problems that they might meet at work but often set in more relatable terms. So rather than presenting school leavers with an impenetrable client case study, they might be asked about more everyday scenarios – divvying up the bill fairly in a restaurant, for example – that test problemsolving, prioritisation and interpersonal skills. “The interview is one part of our selection process, but it can only be one part of it, not the whole thing,” says Gallagher Brown.

Along with the shift to more strengths-based interviews (especially for those candidates with less experience), the other major change in recent years of course is the rise of the virtual or video interview. But whether face to face or online, the interview itself is conducted in more or less the same way, says Gallagher Brown. “We work in an agile way and conduct both sorts of interview. What online interviewing does give us is a degree of flexibility if there are candidates who cannot come into the office for any reason.” The use of digital pre-interview assessments is also on the rise and can add valuable data points that can better inform the interview itself.

If the bad news is that interviews are freighted with flaws and vulnerable to all kinds of biases, the good news is that most of these shortcomings are understood and can be, if not eliminated, at least mitigated. The challenge for employers is to think a bit harder about what they are trying to achieve and to use better-structured interviews as part of a well designed package of assessments, rather than seeing them as the only tool in the box.

So the more extreme ‘pass, fail’ aspects of job interview roulette may recede as a broader range of assessments helps to take the strain. But interviews of one kind or another are likely here to stay. And why not? After all, even the publicity-shy Katharine Hepburn knew that she could not have got where she was without doing at least some interviews. “Of course, I wouldn’t want the press to ignore me completely,” she once grudgingly conceded.

Job interview tales

Interviewer fail

“I wanted to work for [a well-known fashion retailer. One interview question was, I am legit not lying: ‘What is your favourite colour?’ I answered ‘baby blue’, and my interviewer said: ‘Ooh sorry, red is the answer we are looking for,’ and proceeded to show me the exit.”

Candidate fail

“I interviewed someone for a call centre role. We got to the salary part and he called his mum on speakerphone to help him negotiate. He didn’t get the job.”

Plus one smart-but-sneaky interviewer

“I applied to work at a vet. The veterinary surgeon did the interview while he was spaying a cat. I fainted. When I woke up, I was not offered the job”

Now read

Image credits

Sneksy/Getty Images

C.J. Burton/Getty Images

John Moore/Getty Images

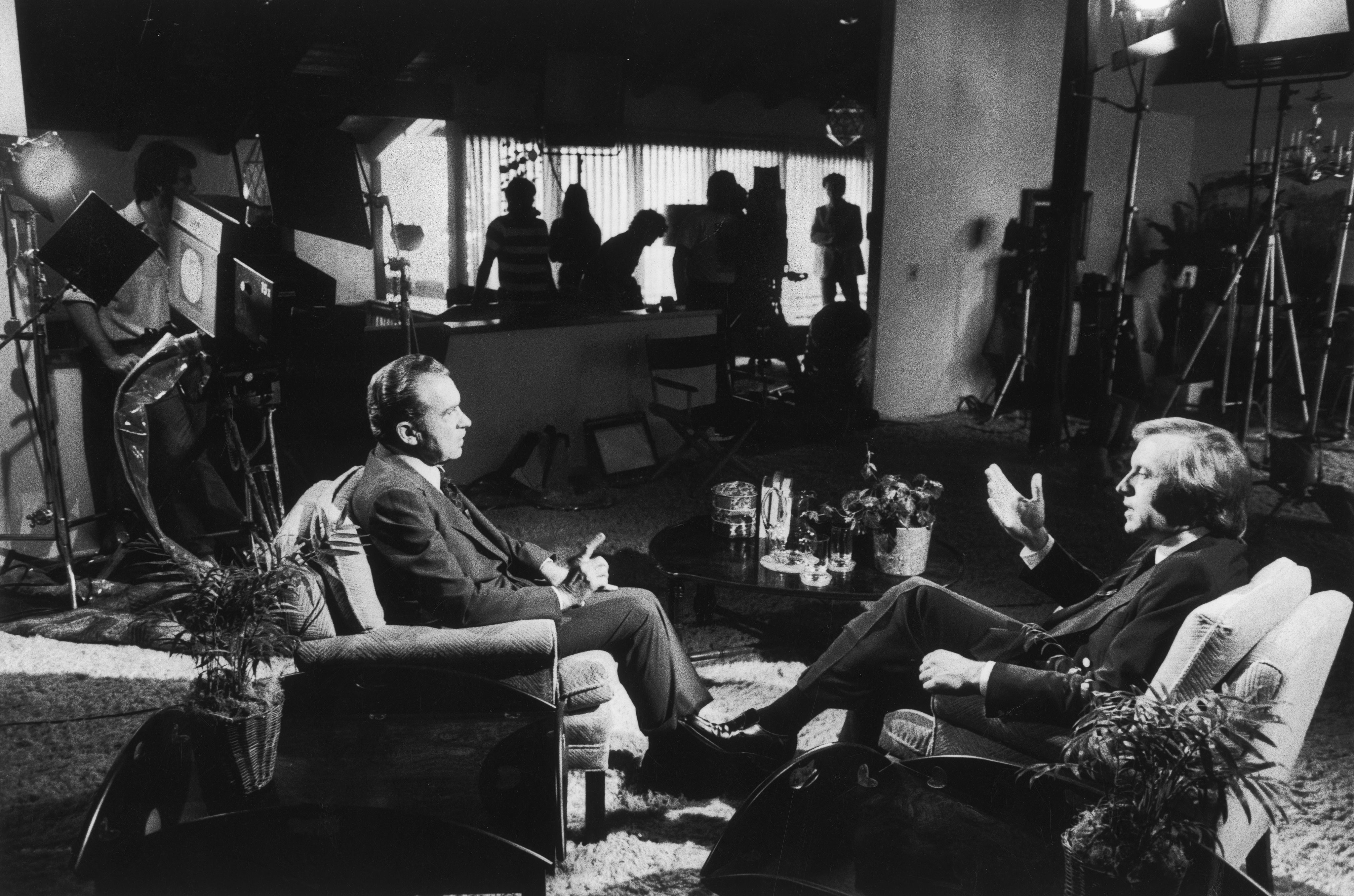

LANDMARK MEDIA/Alamy Stock Photo

John Bryson/Getty Images

Joe Pugliese/Harpo Productions/PA Wire/Alamy

Nick/Unsplash

Sneksy/Getty Images

Manja Vitolic/Unsplash