Premium access: CIPD Festival of Work 2023 content on demand pass

Work. Winter 2021, Issue 31

Does HR need an ROI?

In a world of measurable, manageable data, there is a growing divide between those who want HR to quantify its results and others who see impact on people as the only thing worth counting.

By Jeremy Hazlehurst

You probably don’t see the funny side of Catbert, the evil HR leader from the Dilbert cartoons, who adds a special layer of HR-flavoured misery to an already dismal corporate life. In one typical strip, Dilbert complains to the malevolent red feline that his boss has prevented him from moving to a great job. “That’s outrageous! There shouldn’t be any great jobs in this company,” replies Catbert. “Once again, you’ve made a bad situation worse,” sighs Dilbert. “That’s the human resources promise,” concludes Catbert.

The character struck a chord with readers because for a long time, employees were encouraged by popular culture to view HR as a negative presence in their lives, a rules and policy-obsessed function which asked them to jump through hoops and tick boxes, for reasons they didn’t understand. The reality has, of course, always been far more nuanced than such caricatures could ever communicate. The profession – rightly – tells itself it has consistently shown organisations how to streamline, digitise and evolve for the 21st century without, for the most part, sacrificing their essential humanity. And yet where an impatience with the HR function can still be detected, it is traced by some to a tension between those parts of an organisation whose outcomes and performance are easy to quantify and one where meaningful metrics are harder to come by. You can capture sales, for instance, in a straightforward P&L, but wellbeing and a culture of development and learning opportunities are inherently nuanced and fuzzy, as well as being trickier to ascribe to a single intervention or department. How, in short, does a business know its investment in and prioritisation of HR is actually paying off?

The essential humanity of work has been a staple feature of art through the ages, including John Singer Sargent’s Venetian Glass Workers

The essential humanity of work has been a staple feature of art through the ages, including John Singer Sargent’s Venetian Glass Workers

Though data has democratised the debate, certain schools of HR thought have resisted any move to explain the function or its benefits, believing the business of people management to be somehow above such trivialities and viewing attempts to quantify HR’s effectiveness as reducing a people-focused discipline to little more than another branch of accountancy. It is a conversation that has proven frustratingly counter-productive for decades – but there are signs that is changing, and the driver has been the societal changes wreaked over the past couple of years.

The world of work is, of course, going through a wholesale, once-in-a-generation re-evaluation of what matters. The stranglehold of shareholder value is loosening fast and suddenly, HR is at the centre of everything. “2020 and the global coronavirus pandemic shifted a lot of the previously held views that HR was full of well-intending but ineffective bureaucrats and spoilers, fixated on rules and policies and not in tune with what businesses needed to thrive in a challenging world”, author and consultant Perry Timms explains in his revamped book Transformational HR, capturing a feeling many have identified since the working world was turned upside down by the pandemic.

In The Dinner Hour, Eyre Crowe captures workers relaxing between shifts in Victorian-era Wigan’s thriving textile trade | Album/Artepics/Alamy Stock Photo

In The Dinner Hour, Eyre Crowe captures workers relaxing between shifts in Victorian-era Wigan’s thriving textile trade | Album/Artepics/Alamy Stock Photo

Black Lives Matter was, in its own way, every bit as important in shifting business priorities. “HR – long the guardian of policies, processes and approaches that enable fairness and equity in the workplace – were again turned to by their businesses and leaders: to show support and allyship, to look at their own systems of prejudice and bias, and to create supportive and safe places to work and be,” writes Timms.

Suddenly the “social, spiritual and humanitarian element” of organisations became a focus. Even the most cynical or recalcitrant of businesses understands people are central to productivity and profitability, a point that has been dramatically reinforced by the chronic recruitment issues many organisations have suffered since economies gradually reopened.

Many of these concerns have coalesced around the broad notion of culture – which, though imperfectly defined and contested as a hard measure, encapsulates many of the broad series of interventions HR can make in everyday business life. KPMG, in a 2021 survey of managers and leaders, identified culture as the most pressing strategic priority for businesses, and for two-thirds of respondents HR was the department with the most direct responsibility for the issue. “The conversation around culture is intensifying as senior leaders understand the need for culture change to drive business performance,” says Kate Holt, an HR partner at KPMG.

Austrian graphic artist Rudolf Kalvach is best known for stylised studies of port life in 1900s Trieste, including this piece entitled Harbour Workers | Galerie bei der Albertina Zetter, Wien

Austrian graphic artist Rudolf Kalvach is best known for stylised studies of port life in 1900s Trieste, including this piece entitled Harbour Workers | Galerie bei der Albertina Zetter, Wien

Professor Sir Cary Cooper, author, CIPD president and co-chair of the National Forum for Health and Wellbeing at Work, says wellbeing is the other key strategic driver. “HR has been brought to the fore because we have the issue of how to manage people in hybrid working scenarios, and we have mental health being the leading cause of sickness absence in the UK economy and in most developed countries,” he says.

“So HR is taking the lead all over the place. All of a sudden, I think the leaders of businesses, the people in the C-suite, are taking HR more seriously. You actually hear C-suite people say now that our most valuable resource is our human resource. And who is going to handle that? It’s not going to be the ops manager, it’s not going to be finance. It’s HR. “HR was perceived before this as being about process. Hiring and firing, employment law, covering your backside. But what we are seeing now is not just ‘personnel’, it goes way beyond that,” adds Cooper. “It’s about good work.”

This new attention, while welcomed by commentators, does beg the question: should HR be able to quantify what it does for its money? The function is not unique in lacking a simple metric that encapsulates its activity, but it is striking that most attempts to define one have immediately floundered. Engagement, as a concept, was supposed to represent just such a holy grail, but its precise definition is still hotly debated in the academic HR community. Even if its existence is broadly viewed as a positive, attempts to link it definitively to other measures (such as suggesting engaged employees are more loyal, for example) have never reached a consensus.

Harriet Hounsell, chief people officer at frozen food giant Nomad Foods and former holder of the same role at Marks & Spencer, is among those who resists the attempt to force a broad array of activities into a single metric. “HR teams get out of bed to make a difference,” she says. “Part of that psyche is knowing that they need to be able to explain and discuss how what they do add value. You can’t measure it on the balance sheet the same way that you can some other things, it’s always harder. I wonder if some day we could manage culture, too. I think that’s a really interesting question, but I don’t think we should get too single minded about saying that unless we can see a hard ROI, we don’t do anything. That’s very binary thinking.”

There is also the question of which aspects of HR’s remit can be readily quantified. Time to hire, cost of acquisition and employee turnover are all measurable in the strictest sense but deal only with relatively narrow actions. Diversity is vitally important but goes far further than mere numbers. “Does any function really have the data to prove its ROI?” asks Rob Briner, who as professor of organisational psychology at Queen Mary University of London has worked alongside numerous HR teams looking to add rigour to their practice. “Does marketing? Do sales, or operations, really have good quality data? They might have lots of numbers, but sometimes they are measuring silly things. People might tell you that they have a great Net Promoter Score, or 20,000 customer reviews, but unless they can tell you what that means, if it is actually helping the organisation, it is meaningless. People sometimes measure things that don’t matter, just because they can.”

Real ROI is about how much a function – HR or otherwise – is really contributing to organisational goals, says Briner. “Every function has its own techniques, its own skills and specialisms. The question is, are they helping the organisation to achieve its objectives?” Briner’s academic focus in recent years has been around making HR more evidencebased – which doesn’t mean deploying data to justify investment decisions or trac performance but ensuring the reasoning behind HR interventions is sound. For him, this is a more important principle than ROI and an area in which HR is rapidly developing – and rather than focusing on the reason for its own existence, the function would be better developing the confidence to experiment and make mistakes without rushing to justify itself, he adds.

“Admitting that you have made mistakes is a sign of a department’s maturity and in my experience HR is not quite there,” Briner says. “It isn’t yet quite bold enough to say to the senior management team ‘well we did this thing, we did this training or we introduced this policy and we spent half a million pounds on this programme but it didn’t work’. Or even that it made things worse, so we are going to stop doing it now. “At the moment everyone thinks ‘Oh my God, they’re going to think HR is terrible’. But until you reach that point, until you are able to admit that some of what you are doing is not working, you will never be able to properly evaluate yourself.”

It isn’t ROI, even in the broadest sense, but it is a way of assessing the maturity of the HR profession that even the most cynical business leader could get behind. Until then, the debate over quantifiable HR metrics seems set to rage on.

Where’s the evidence?

Four studies HR can cite to prove its effectiveness

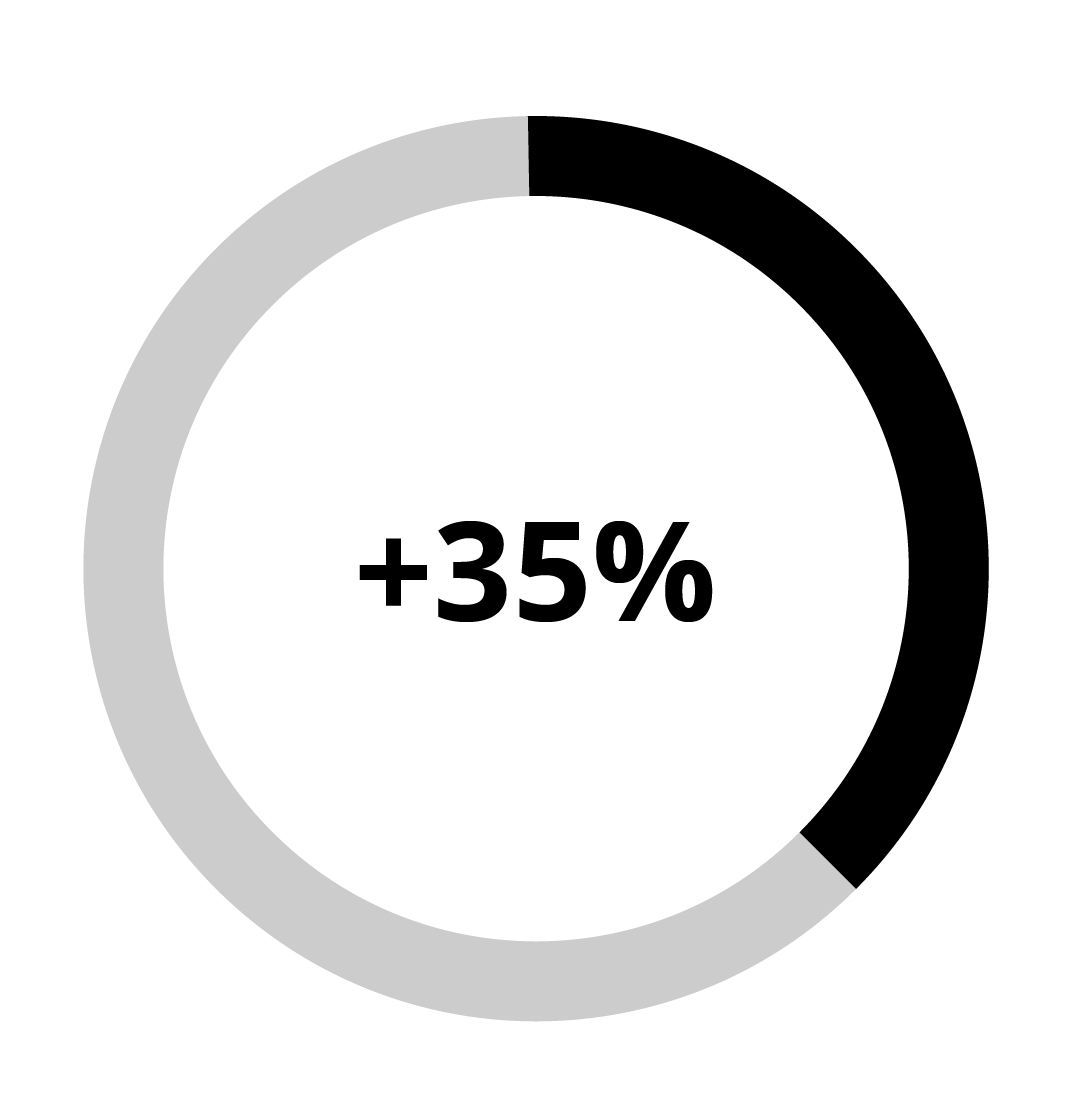

Diversity boosts the bottom line

McKinsey research, titled Why diversity matters, found that the most racially diverse firms were 35 per cent more likely to have financial returns above their respective national industry medians.

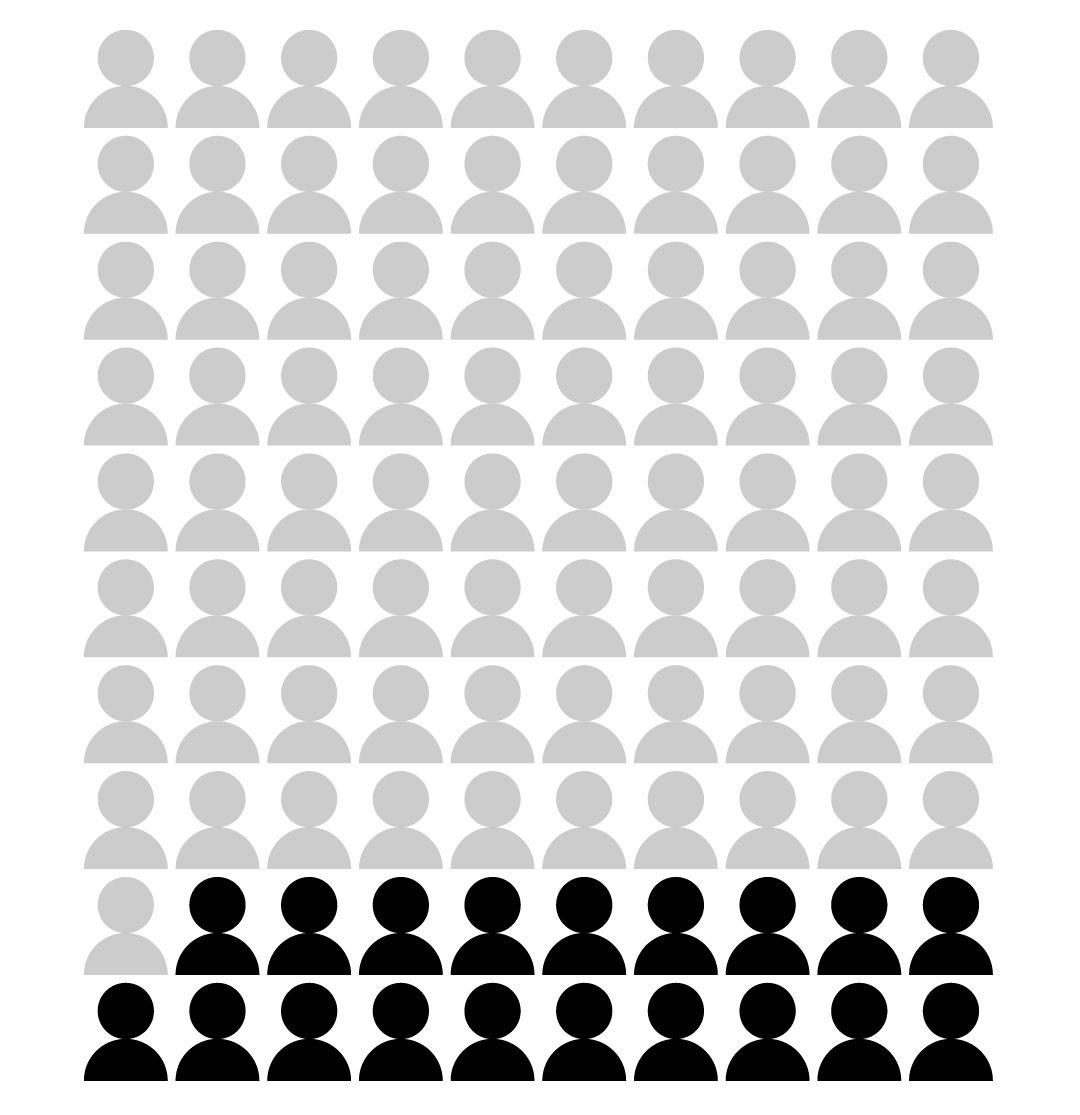

Engaged employees are productive

According to a Gallup study of 2.7 million employees, those who are defined as engaged at work report 81 per cent less absence, and their departments are 23 per cent more profitable than the Median.

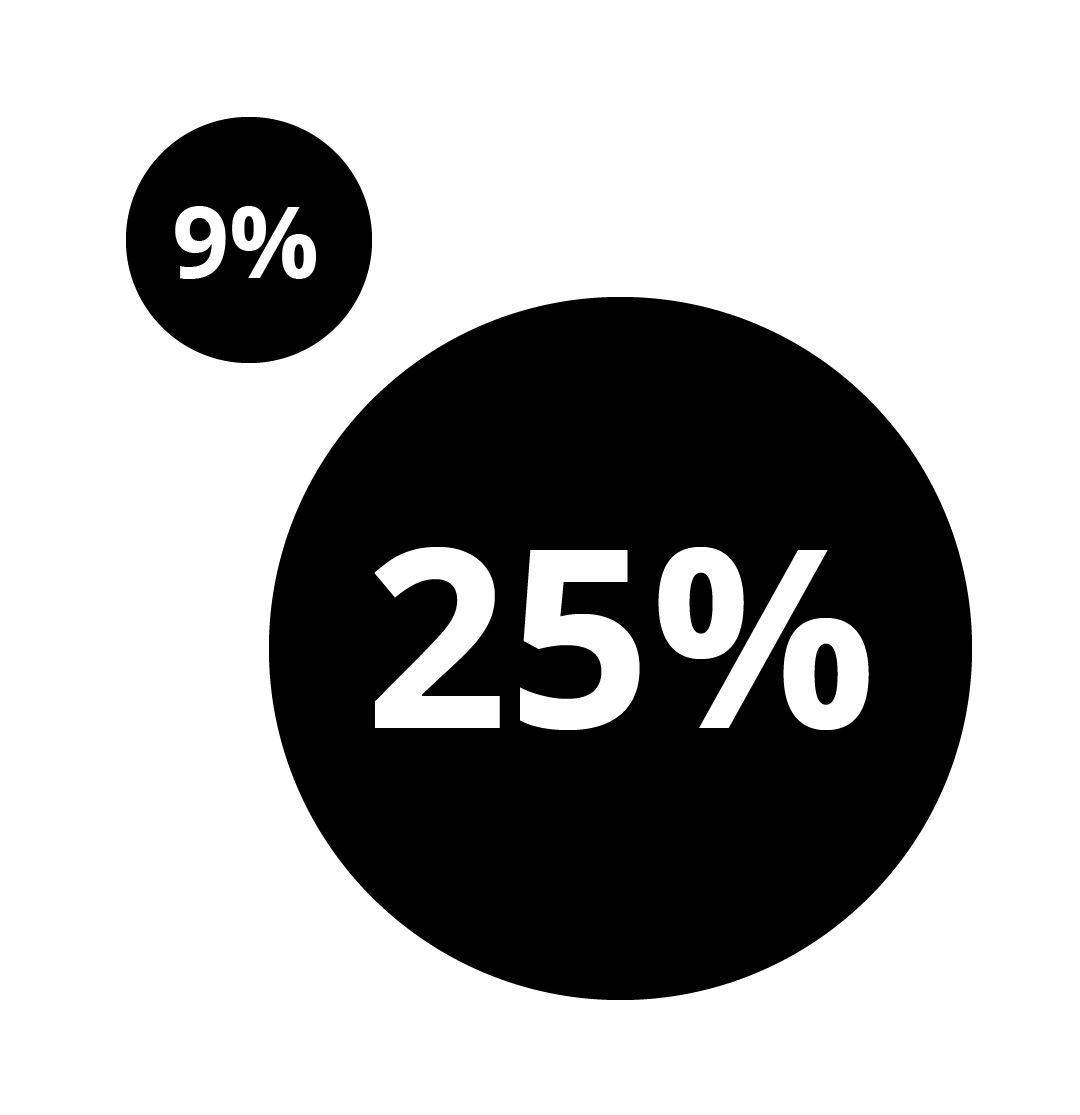

A positive work environment helps staff retention

Mental health charity Mind says 9 per cent of people have resigned from a job due to stress and 25 per cent have considered resigning due to the pressure of work. By its reckoning, work is the greatest cause of stress for most people.

A positive culture keeps the costs down

Firms with reputations as bad employers have to pay 10 per cent more to hire people, according to a LinkedIn study. And nearly half the people surveyed said that they would never apply for a job in a firm with a poor reputation.

Now read

Image credits

The Dinner Hour Wigan by Crowe Eyre - Artepics/Alamy Stock Photo

Harbour Workers by Rudolf Kalvach - Galerie bei der Albertina Zetter, Wien

Venetian Glass Workers by John Singer Sargent - Album/Alamy Stock Photo

Textile Workers (oil on board) by Cliff Rowe - People's History Museum/Bridgeman Images