Premium access: CIPD Festival of Work 2023 content on demand pass

Work. Spring 2023, Issue 36,

It might seem safer for bosses to keep quiet on emotive issues such as abortion, racism and LGBTQ+ rights. But the tale of ex-Disney CEO Bob Chapek shows that sometimes you have to speak out

By Jeremy Hazlehurst

A kiss is just a kiss. Except when it is between two female cartoon characters, it seems. The recent Disney prequel to the Toy Story franchise, Lightyear, was plunged into controversy when it turned out that a tender peck between a female character and her long-term partner had been edited out of the movie, and replaced with an “awkward handhold”. The decision to cut the scene was a sop to conservative Americans but was greeted with outrage from Disney employees, who, understandably, were unhappy that the company was content to depict talking mermaids and aliens on spaceships fighting laser battles, but baulked at depicting gay people, despite having been a famously welcoming environment for LGBTQ+ workers for decades.

Eventually, that kiss was put back into the Lightyear film. And Disney is making strides towards a more inclusive look in all of its products. Its 2019 High School Musical film features two same-sex relationships, and in 2020 it released both Out – a short animated film about a gay man who has not yet come out to his parents, and finds his mind swapped with his dog’s – and Onward, featuring a lesbian character. Even The Rise of Skywalker, a Star Wars film made by Disney, featured a lesbian kiss. British comic Jack Whitehall starred as “the first Disney gay man” in the Jungle Cruise film, too.

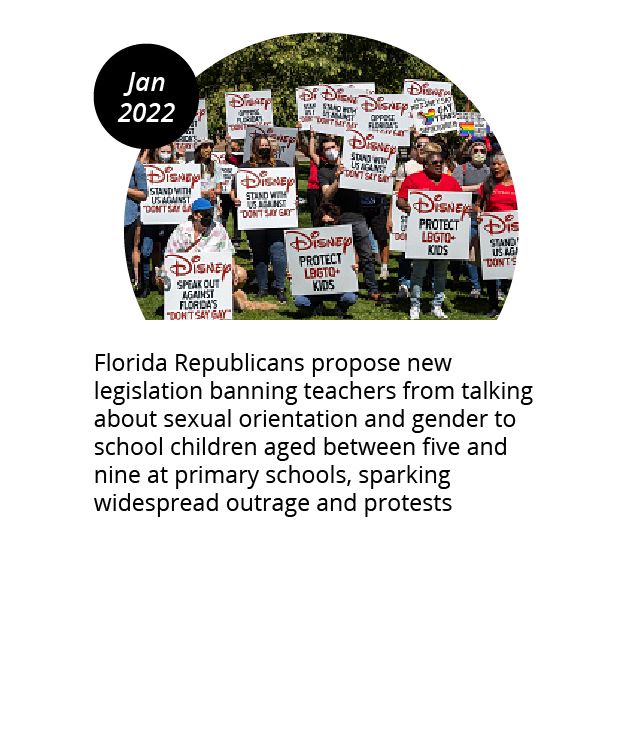

So, things are changing at Disney. But the cultural environment in the US is tricky for a CEO to navigate, and its newfound confidence about LGBTQ+ characters did not please everyone. In January 2022, things got a whole lot harder when Florida republicans proposed a new piece of legislation, the Parental Rights in Education Bill, which among other things would ban teachers from talking about sexual orientation and gender to children aged between five and nine in primary schools. The bill was loudly supported by firebrand Florida governor Ron DeSantis, who wants to become president in 2024 and is keen to appeal to Donald Trump supporters. Liberals and LGBTQ+ people were outraged, and the proposed law was soon dubbed the Don’t Say Gay bill.

LGBTQ+ Disney employees were incensed, and had high hopes that their then new CEO, Bob Chapek, would condemn the proposed law. Previous chief exec Bob Iger, a liberal-minded Hollywood bigwig, had been outspoken in his support for LGBTQ+ staff. And the company had been a trailblazer in equal rights – it was one of the first firms in the US to offer healthcare benefits to the same-sex partners of its employees back in 1995. Furthermore, it has for decades been entwined with Florida politics and has clout. Disneyland is a huge contributor to the state’s economy and was largely responsible for turning it into a tourist destination. It employs 38 lobbyists and had donated more than $30m to state politicians in the last election cycle, including around $100,000 to DeSantis between 2019 and 2021. Disney had financially supported many – if not all – of the Don’t Say Gay bill’s sponsors and co-sponsors, including Dennis Baxley, a Republican who had notoriously voted against allowing gay couples to adopt and other pieces of pro-LGBTQ+ legislation. The only plausible reason that Disney was holding its nose and throwing money at individuals whose views conflicted with its internal company culture was that it could influence those lawmakers on issues that mattered to it.

But, crucially, Disney’s LGBTQ+ employees didn’t just want their employer to hammer out a deal in a smoke-filled room. For them, Don’t Say Gay was an outrage, a direct existential attack on them. Given that the firm was making steps towards embracing LGBTQ+ people in its films and was very (and genuinely) supportive internally, they expected it to publicly condemn the bill. The expectation was even higher because in the past decade a series of other high-profile CEOs had made public statements about political issues close to their – and their employees’ – hearts. In 2012 Lloyd Blankfein, then CEO of Goldman Sachs, advocated in favour of equal marriage; Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, has been vocal about LGBTQ+ rights; and PayPal president and CEO Dan Schulman campaigned against a North Carolina law saying that transgender people had to use the bathrooms for people of their birth gender.

“Our jobs as CEOs now include driving what we think is right... Not exactly political activism, but action on non-business issues”

For a while in the 2010s, it felt like everyone was at it. Some CEOs felt it was part and parcel of their role. “Our jobs as CEOs now include driving what we think is right… It’s not exactly political activism, but it is action on issues beyond business,” Brian Moynihan, Bank of America’s then CEO, told The Wall Street Journal. Perhaps the most famous example of chief execs making political statements was the 2019 statement by the Business Roundtable – an association of powerful American CEOs – committing to long-term stakeholder capitalism, and publicly ditching the old shareholder maximisation mantra. And it was not only liberal CEOs speaking their minds – several conservative business leaders also advocated for their views (see box on page 25).

So there was precedent and yet, from Disney, on this issue that was so viscerally important to so many of its people, there was tumbleweed. Behind the scenes, its leaders were feverishly deciding what to do. Executives at the company were aware of the Don’t Say Gay issue, and the strength of feeling among their workforce. As early as the start of February 2022 there was internal discussion about making a public statement to placate angry employees. Advocacy group Human Rights Watch had been circulating a letter condemning the law, which had been signed by businesses such as Apple and Amazon. According to a Financial Times report, some members of the senior leadership team lobbied to add Disney’s name to the letter. However, the idea was reportedly kiboshed by the new head of corporate affairs, Geoff Morrell, a registered Republican. He apparently argued that the Disney brand was “unifying” – presumably meaning it is not seen as inherently aligned with either Republican or Democrat values – and that the company would be better off using the lobbyists it employed to work in the shadows to smooth the edges off the bill, or even to scupper it.

While the top brass prevaricated, the workers were becoming militant. There were protests, public statements and furious tweets. Animator and director Dana Terrace, who created animated series The Owl House, did a livestream to raise money for charities that support young LGBTQ+ people, in which she said: “Working for this company has... made me so distraught… I hate having moral quandaries about how I feed myself and how I support my loved ones.” The relationship between the company’s leadership and its employees was fraying.

By the end of February, still Disney had said nothing. Then, on the day discussion of the bill began in the Florida Senate, Iger retweeted a statement by President Joe Biden condemning the “hateful” bill. “I’m with the president on this. If passed, this bill will put vulnerable, young LGBTQ+ people in jeopardy,” he wrote. Clearly, this cast Chapek’s fence-sitting strategy in an even worse light. He was probably still hoping that all those expensive lobbyists would manage to schmooze and arm twist their way to a resolution in the Senate, and it is true that a Republican tabled an amendment that would tweak the bill so that, instead of banning classroom discussion of “sexual orientation or gender identity”, it would mention “human sexuality or sexual activity”. But this was easily outvoted.

Finally, on 4 March Disney told USA Today: “We understand how important this issue is to our LGBTQ+ employees and many others. For nearly a century, Disney has been a unifying force that brings people together. We are determined that it remains a place where everyone is treated with dignity and respect.” This was fleshed out three days later when Chapek sent a memo to all Disney staff explaining its position. “I want to be crystal clear,” he wrote, “I and the entire leadership team unequivocally stand in support of our LGBTQ+ employees, their families and their communities… I do not want anyone to mistake a lack of a statement for a lack of support.”

Then came the explanation for the company’s silence. “We all share the same goal of a more tolerant, respectful world. Where we may differ is in the tactics to get there. And because this struggle is much bigger than any one bill in any one state, I believe the best way for our company to bring about lasting change is through the inspiring content we produce, the welcoming culture we create and the diverse community organisations we support.” He added: “As we have seen time and again, corporate statements do very little to change outcomes or minds. Instead, they are often weaponised by one side or the other to further divide and inflame. Simply put, they can be counterproductive and undermine more effective ways to achieve change.”

Predictably, this did nothing to quell employees’ anger. A few days later Chapek felt compelled to send out a further note, this time toning down the ‘it’s complicated’ rhetoric and unambiguously accepting that the company had made mistakes. “You needed me to be a stronger ally in the fight for equal rights and I let you down. I am sorry,” he wrote. He also said the firm would take a hard look at the campaigns it was funding, and immediately stop funding politicians. Just as predictably, all of this gave political ammunition to hardline Republicans. DeSantis called the company “woke”, and said that Disney was “going to criticise the fact that we don’t want transgenderism in kindergarten and first-grade classrooms”. He added: “That’s the hill they’re going to die on.”

In November 2022, Chapek was fired as CEO of Disney, and was replaced by his predecessor, the now 71-year-old Iger. Speaking up about controversial issues surely has it risks, but there can be no clearer proof that failing to speak up can also cost you dearly. In short, it was – is – a mess. But what should the Disney hierarchy have done? It is tempting to say CEOs should just keep their views to themselves, not least because customers don’t seem to care much. Research by Weber Shandwick and KRC in 2016, at the height of the activist CEO wave, found that 31 per cent of people surveyed had a ‘more favourable’ view of a CEO if they took a stand on ‘hotly debated current issues’, with 22 per cent saying they felt less favourable towards them. However, it seems this depends on the issue. When a stand taken was ‘not tied to company business’, then the approval number fell 11 percentage points to 20 per cent, while the number disapproving rose 10 percentage points to 32 per cent. But 37 per cent and 38 per cent of people said activism either made no difference to their perception of the CEO, or they didn’t know.

But often, when CEOs speak up they are not talking to customers, but to their own people. Chris Salt, co-founder of City PR firm Headland, does not like the ‘activist CEO’ moniker. “For me what is actually important is having an authentic CEO – that leaders have in mind lots of stakeholders and primary among those are the employees, because when CEOs are thinking about them, they are thinking about what people come to work for and the business’s purpose,” he says. “It’s good when the CEO stands for something, has a certain set of values and talks about that internally. And, vitally, I think employees want to see their CEOs advocating for those values externally, too. So I think CEOs publicly talking about their values is a positive thing – not because I want them to be ‘activist CEOs’, but because they’re being authentic about what their companies do and their place in society.”

Standing up for your values is not for the fainthearted, however, and the opinions of those outside the company cannot be discounted. Salt says CEOs who speak up will inevitably be criticised, and need to be ready for that, and they can only expect their interventions to be successful if their company’s financial performance is good. If it is not, that will be blamed on their ‘activism’. “Problems arise if the CEO starts talking about things that are not linked to the business’s purpose,” says Salt. “Then it becomes ego driven and inauthentic. That is what I would call a true ‘activist CEO’. And that is when you start to lose the stakeholders who matter most: the employees, investors and partners.”

Keeping these core stakeholders happy is vital but, as the Disney fiasco shows, problems start when leaders fail to balance their needs and desires with those of other, more hostile groups. “LGBTQ+ issues are very central to Disney’s core values, so it’s something they cannot shy away from,” says Dimitrios Spyridonidis, associate professor of leadership and innovation at Warwick Business School. “But at the same time, the people at the strategic apex of organisations cannot really ignore powerful forces that operate against them from the political domain, especially ones that can have severe implications for the way they run their organisation and can threaten their financial stability.”

Spyridonidis says leaders can adopt a ‘paradox mindset’ and, rather than choosing between different courses of action, must find a way to balance contradictions: “The idea is that you can be true to your values and purpose, but not at the expense of financial stability or keeping powerful politicians happy.” The challenge for HR, he says, is that you need to develop people with this outlook not only in leadership positions, but throughout the organisation. “You need people who can work with this tension,” says Spyridonidis. “It can be about storytelling; telling the story from a different perspective to satisfy a broader set of stakeholders rather than just one or the other. It can be difficult for employees, but that’s down to leadership having the mechanism in place to explain to people with transparency the rationale behind decisions and getting buy in. These are hazy, messy issues, and you don’t lead an organisation in a vacuum.”

Disney’s travails demonstrate just how hard this can be. Advocating for a set of values internally is relatively easy. But it creates an expectation that the advocacy will continue outside the company’s own four walls and internal comms. And that portion of the world can be harder to persuade. Both Salt and Spyridonidis say they like to see CEOs standing up for what they believe in. The old days when they could hide behind the mantras of ‘profit maximisation’ and ‘fiduciary duty’ and leave politics to the politicians are long gone. Leadership no longer stops at the front lobby. Be brave, but tread carefully.

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Culture wars and Disney

Five activist CEOs

Marilyn Carlson Nelson, Carlson

The chief executive of Carlson Companies, which owns big hospitality brands such as Radisson and TGI Friday’s, ensured that her firm was the first US travel company to sign up to the Tourism Child-Protection Code of Conduct, an industry initiative designed to help combat people trafficking. She also insisted that desk employees were trained to look for the signs of abuse and exploitation in children who come to their hotels.

Lloyd Blankfein, Goldman Sachs

In 2012 Blankfein appeared in a video for the Human Rights Campaign, a US organisation that advocates for LGBTQ+ rights, saying: “I’m Lloyd Blankfein… and I support marriage equality.” A Californian ban on gay marriage was overturned several days later, laying the groundwork for the US Supreme Court to recognise gay marriage in 2015.

Susan Wojcicki, YouTube

In 2016, then-President Trump enacted a ban on immigrants coming to the US from several majority-Muslim countries, and millions of refugees who were fleeing war in Syria. This led Wojcicki to describe her own family’s harrowing journey to the US as refugees in 1949: “Despite what some have argued, these refugees are not terrorists seeking to inflict harm – in many cases they are families escaping terrorism. They are families who, like my family, risked their lives in hopes of offering their children a better future.”

Marc Benioff, Salesforce

Benioff agitated against proposed laws in several US states that would have dictated which bathrooms trans people could use. “Today CEOs need to stand up not just for their shareholders, but their employees, their customers, their partners, the community, the environment, schools, everybody,” said Benioff.

David Green, Hobby Lobby

Activist CEOs do not all follow a liberal agenda. Green, a Christian who runs his craft firm on faith principles, objected to a clause in the Affordable Care Act – commonly known as ‘Obamacare’ – that said an employer must pay for employees’ birth control. He argued that a business ought to be able to opt out of doing things to which it is fundamentally opposed, and he was against drugs that would prevent a fertilised egg from embedding in the uterus wall, on the grounds that life begins at conception. The case went to the US Supreme Court in 2014, and Hobby Lobby won.

How to speak up

Choose your issues

Some, like anti-racism, are so engrained in corporate cultures that leaders feel confident decrying them. Others, though, can be trickier, and CEOs should discuss what matters to them and why, write Aaron K Chatterji and Michael W Toffel, two Harvard Business School academics in a Harvard Business Review article. A 2018 survey found that 80 per cent of people questioned felt it was appropriate for CEOs to discuss minimum wage, pay equality and political issues that affect business, while only 40 per cent felt comfortable with them weighing in on abortion, the legalisation of drugs and transgender issues. Concerns around immigration are particularly tricky, although CEOs who are immigrants themselves might feel compelled to speak out.

Weigh up the consequences

CEOs should “balance the likelihood of having an effect and other potential benefits – such as pleasing employees and customers – against the possibility of a backlash”, say Chatterji and Toffel. Polarising issues carry higher risk than issues like parental leave or the benefits of STEM education, which people expect CEOs to opine about.

Time your intervention wisely

It is far easier to prevent a piece of legislation passing, than getting it rescinded afterwards. Also, the first to stand up tends to get more attention. The first CEOs to leave President Trump’s economic advisory board after he refused to condemn the Charlottesville rioters got all the headlines and credit.

But realise there’s safety in numbers

More than 160 CEOs signed a letter by the Human Rights Campaign opposing the North Carolina bathroom law, meaning that individuals attracted less opposition. Dozens of CEOs signed the Business Roundtable letter on stakeholder capitalism, giving the impression of a non-controversial consensus.

Make sure stakeholders are aligned

“Though CEOs first have to decide whether they’re speaking for themselves or for their organisations, they should recognise that any statements they make will nonetheless be associated with their companies,” write Chatterji and Toffel. Discussing what you will say with the relevant experts in your organisation is essential.

Now read

Image credits

Strizh/iStockPhoto/Getty Images

Roberto Machado Noa/LightRocket/Getty Images

Caelestiss/iStockPhoto/Getty Images

General Photographic Agency/Getty Images

Mark Peterson/Corbis/Getty Images

Bob Riha, Jr./Getty Images

Tony Ranze/AFP/Getty Images

Katie Rice/Orlando Sentinel/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Cinematic Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

Moviestore Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

TCD/Prod.DB / Alamy Stock Photo

GIORGIO VIERA/AFP via Getty Images

THA / Alamy Stock Photo

Daniel A. Varela/Miami Herald/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Alisha Jucevic/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Image Group LA / Contributor/ Getty Images

Celal Gunes/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Stephanie Keith/Getty Images

Taylor Hill/FilmMagic/Getty Images

Mireya Acierto/Getty Images

Amy Sussman/Getty Images

Drew Angerer/Getty Images