Premium access: CIPD Festival of Work 2024 | Digitally exclusive to content+

Work. Winter 2023, Issue 39

Who decides who does what at work?

The way we assign tasks today has a critical impact on productivity and morale – and is much more complex than in factories of old. Yet the concept is still hugely underexplored

Words Jane Simms

The 1992 film Glengarry Glen Ross is famous for many reasons – not least its profanity: the cast referred to it jokingly as ‘Death of a Fuckin’ Salesman’. Adapted from David Mamet’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, the tragicomedy stars Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon, Alan Arkin and Ed Harris as desperate, unethical real estate salesmen, whose jobs are on the line. The show-stealing scene features Alec Baldwin as ‘Blake’, parachuted in ‘from downtown’ to gee up the team. He lets rip a storm of invective, the brunt of it directed at Lemmon’s character – Shelley ‘The Machine’ Levene, a pathetic has-been. Levene is pouring himself a coffee at the back of the room when Blake roars the immortal line: “Put. That. Coffee. Down.” Coffee, he explains menacingly, “is for closers”.

The central irony of the film is that the salesmen are trying to make a living out of ‘dead-beat leads’ – but ‘the boss’, who insists “I don’t make the rules”, will give new high-quality leads only to ‘closers’. “We work too hard. What do you do, what can you do, if you don’t have the leads, if you don’t have the goddamn leads?” asks one of the salesmen. Only top salesman Ricky Roma (Pacino) gets the good leads, he complains – “but he doesn’t need ‘em!”

We would all like to think work does not work that way today – but in some senses it does. We may have fewer psychopathic or ineffectual bosses, but the way tasks are allocated tends to be random and reactive, leaving many employees feeling overworked and undervalued. Indeed, the very concept of work allocation – who gets to do what, and why – seems to be undervalued too. When she was researching her 2022 book, The No Club: Putting a Stop to Women’s Dead-End Work, Linda Babcock, professor of economics and head of the social and decision sciences department at Carnegie Mellon University, was shocked by the dearth of research on the concept.

How employees allocate their time across tasks “is perhaps the most important business decision, so getting it right has real consequences for the organisation’s health and prosperity”, says Babcock. Work allocation affects five key business objectives that drive productivity and profits: utilising the workforce efficiently; creating a culture where everyone pitches in; satisfaction and engagement; retaining valuable employees; and attracting the best talent. On the face of it, it seems simple, as Rob Briner, professor of organisational psychology in the School of Business and Management at Queen Mary University of London, points out: “If someone is good at something it makes sense to give it to them rather than someone who isn’t good at it.” But, as he admits, “even that basic logic doesn’t make much sense. We want people who aren’t good at it to get better at it, because the person who’s good at it might leave.”

Sharon Parker is a professor in the Centre for Transformative Work Design in the Future of Work Institute at Curtin Business School in Australia, and a leading researcher in the field of job design. When asked why work allocation is not a field of study in its own right, and whether it should be, she responds: “Generally I would say that task allocation stems from the way work is designed and the leader behaviour.” But in a knowledge and service economy and a rapidly evolving business climate, work design is in itself an increasingly complex challenge.

It used to be so simple. Consider this description from Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, of how pins should be manufactured. “One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head: to make the head requires two or three distinct operations: to put it on is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about 18 distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometime perform two or three of them.” Smith believed that if jobs were specialised and simplified to the greatest practicable extent, employees would be able to hone their job-related skills and devote their full attention to very few tasks, maximising efficiency and productivity.

This way of thinking led to the ‘scientific management’ philosophy outlined in 1911 by Frederick Taylor. ‘Taylorism’ involved designing entire work systems with standardised operations and simplified, repetitive tasks, so that employees had little personal discretion (whether making pins, matches or cars). People could be easily trained and were readily replaceable. By the 1950s most manufacturing jobs were designed according to the principles of scientific management. Unsurprisingly, workers kicked back.

Boredom led to stress, injury, absenteeism, turnover and strikes – negating the very efficiencies the system was intended to promote. New approaches to job design emerged, many of them based on the work of Frederick Herzberg in the 1960s, who argued that, to motivate employees to do good work, jobs should be enriched rather than simplified.

Parker herself has developed a SMART Work Design model, which captures evidence from hundreds of research studies into how to make work both healthier and more productive. The acronym stands for stimulating (varied, interesting and challenging), mastery (role clarity and feedback), agency (autonomy, control and influence), relational (support and connections with others) and tolerable (manageable job demands). Task allocation is ‘baked in’ to the role, explains Parker. But she says more needs to be done to embed the theories into practice.

There have been many attempts to do this, but none has proved entirely successful. Interest in ‘job crafting’, where employees help to shape and customise their own work, emerged in the 1990s. It was supposed to increase person-job fit, but it created a different type of unfairness: only some people got to do more of the things they liked and less of the things they did not – the rest became over worked and demotivated, compromising the effectiveness of the team. Aside from the high-profile example of zany online US shoe and clothing retailer Zappos, holacracy – where teams design and govern themselves – has not caught on either. When Zappos introduced it in 2015, 18 per cent of employees left, 6 per cent of them citing ambiguity and lack of clarity around progression, compensation and responsibilities. Linda Holbeche, an expert in leadership, human resource management and organisation design and development, observes: “The role of managers is supposedly redundant in this brave new world but, ironically, holacracy is a very top-down approach.”

It seems that employees want some freedom but not too much, which requires a very particular, sophisticated kind of line management. As Herzberg pointed out, when jobs are enriched ‘good supervisory practices’ should be a hygiene factor. Yet many managers these days are neither trained to manage people nor have enough time to do it. So their default tactic is to allocate complex and challenging projects to high-performing team members – with negative consequences for work quality, team dynamics and employee wellbeing. Referring to her SMART model, Parker explains: “If, for instance, women were regularly asked to be the token woman on committees, or to write up meeting notes, the additional demands on them could create low tolerable and low stimulating work. And if men, say, were given lots of interesting and stimulating work, their work is SMARTer, with all the opportunities for growth and development that go with that.”

And, it turns out, gender-based job allocation is far from hypothetical (as is, of course, discriminatory decision making based on race, class and many other characteristics besides). In her 2001 book, Bias Interrupted, Joan Williams, director of the Center for WorkLife Law and professor at the University of California, writes: “In industry after industry, we find that white men overwhelmingly feel they have fair access to desirable assignments (81 per cent to 85 per cent say so)… Women and professionals of [colour] are 18 to 32 percentage points less likely than white men to say their access to desirable assignments is fair.” Managers justify the status quo by saying there are only a few people with the skillsets or networks to get the job done – which, says Williams, is an admission both of their own failure and the vulnerability of the organisation.

But if a fairer distribution of ‘glamour assignments’ and non-promotable tasks is the low-hanging fruit of work allocation, what can HR do to reach higher up the tree? The resounding answer seems to be to teach managers how to coach. Freed from traditional ‘directing’ behaviours they can think carefully about how to allocate jobs. Alastair Gill, founder of Alchemy Labs, where he helps companies seed disruptive change, believes the role of managers today is building relationships based on mutual trust. “It’s about coaching, not command and control,” he says. “It’s about the quality of the conversations you have with your direct reports, every week, about where they are with their work, if anything is getting in the way, how you can help them and discussing the next task.”

Because businesses are mired in bureaucracy – characterised by endless meetings and video calls – they lack the time to even think their way out of it, says Gill. “Busy is the new stupid,” he says. “It’s not just about what jobs you give people to do, but whether jobs need doing at all. My advice is take an hour out of your week to work out what you are doing with the other 49 and whether that contributes to the business.”

But for all the thinking and best practice around meaningful work, career paths, psychological safety and community that has emerged over the past 20 years, Holbeche notes two trends that threaten to reverse that progress. In the digital era, where you can buy something off Amazon at 6pm and have it delivered by 8am the next day, many tasks have to be fragmented and repetitive to deliver the speed and efficiency that requires. And thanks to the gig economy, the work is also precarious. “It’s sort of Taylorism with knobs on, because you’re breaking down tasks in the old way, but you’ve dismantled the job security that went along with it,” she says.

Companies like Amazon have been described as ‘the new factories’. But that is to do actual factories in the 21st century a disservice. They may not grab the headlines, but many modern businesses have left the bad old days of Taylorism far behind them and are now highly successful employers with leading-edge working practices. Can they also teach us something about how to allocate jobs more effectively in knowledge and service industries?

It is a model that is about as remote from the poisonous (albeit fictional) profanities of Glengarry Glen Ross as it is possible to imagine, and all the better for that. Life may imitate art, but work does not have to.

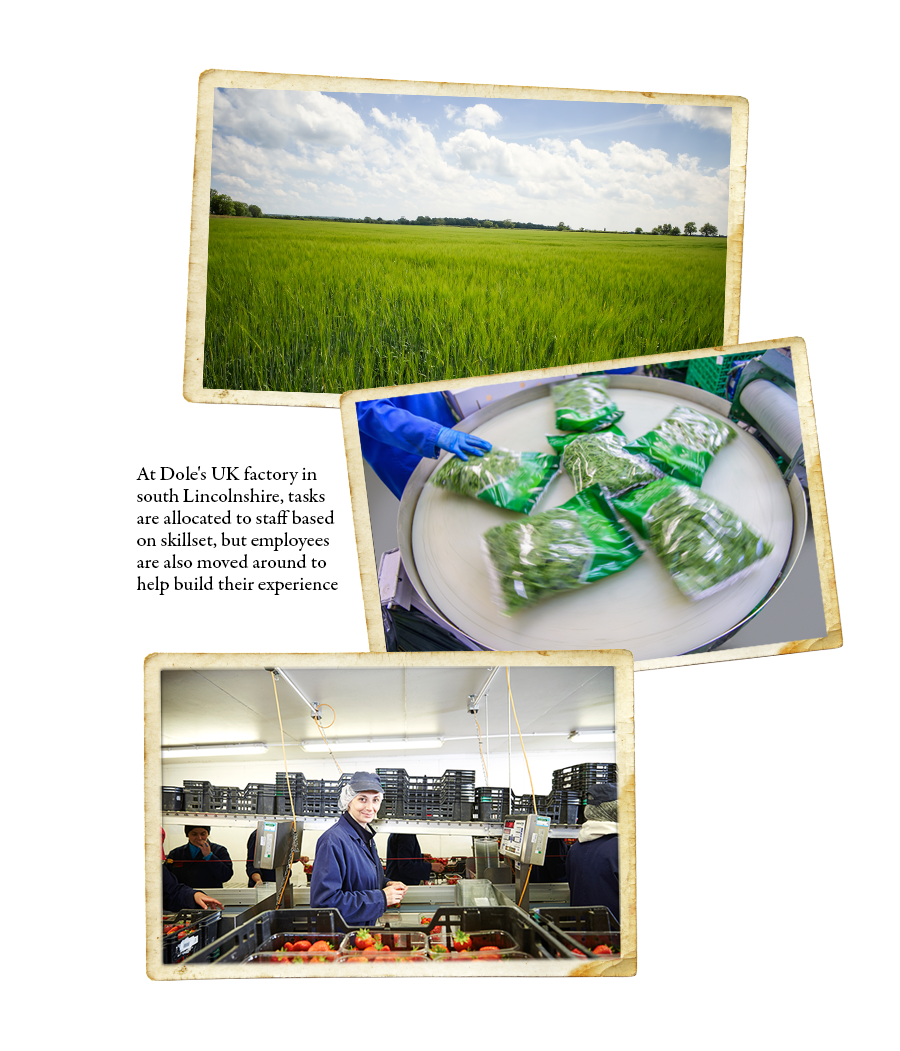

Multinational fresh produce company Dole’s UK factory sits on an unremarkable industrial estate just outside Spalding, among the flat fertile fields of south Lincolnshire. The sense of calm and order in the production area belies the complexity of the business, which operates 24 hours a day, 364 days a year, to move 254 product lines – from fine beans and baby corn to kale and kiwis, from drinking coconuts to M&S party food – in and out of the facility. Produce arrives from all over the world and Dole unpacks it, repacks it, ripens it, repacks it again, stores it and distributes it at a rate of around one million packs a week, to customers including major supermarkets and wholesalers.

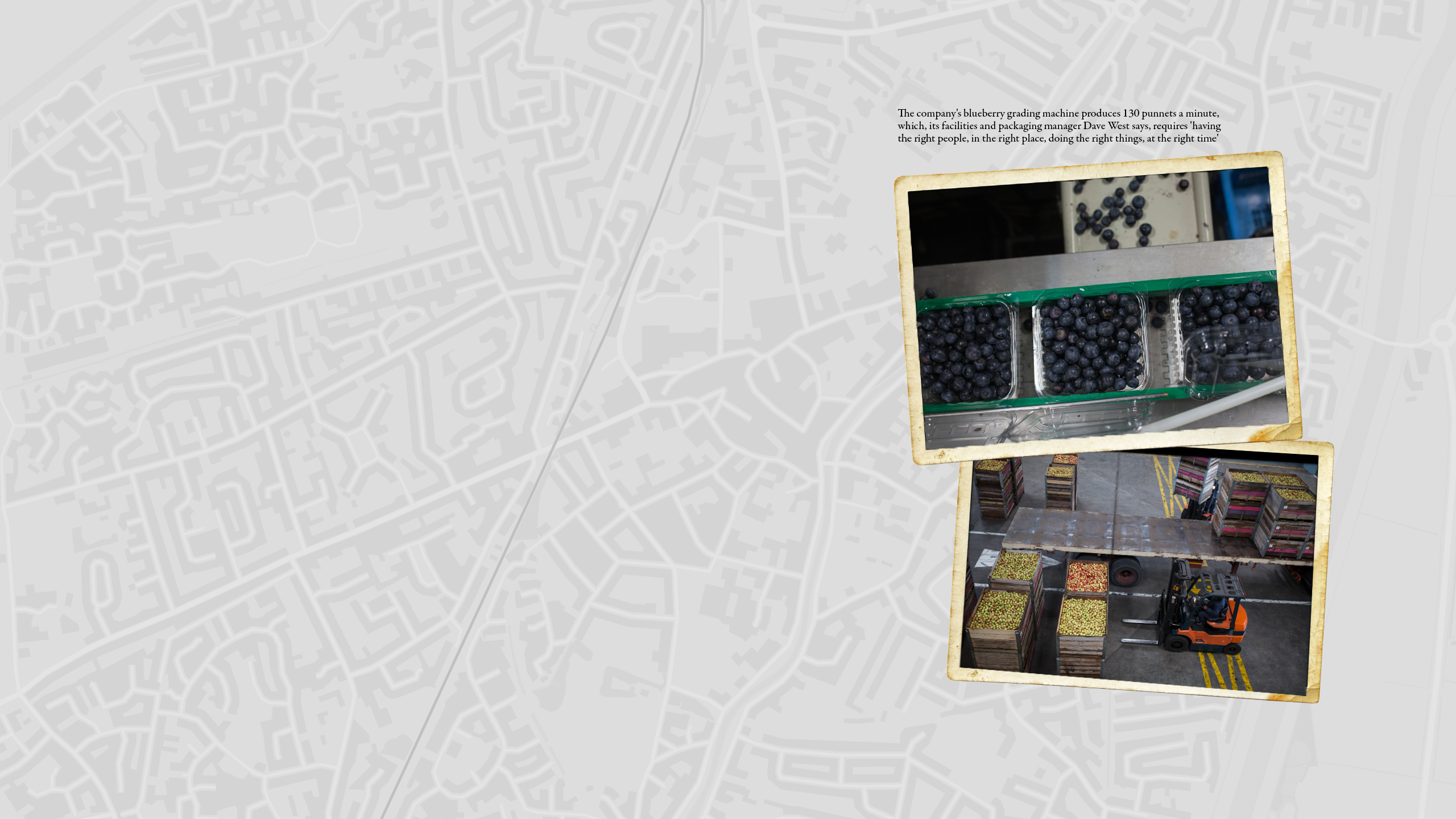

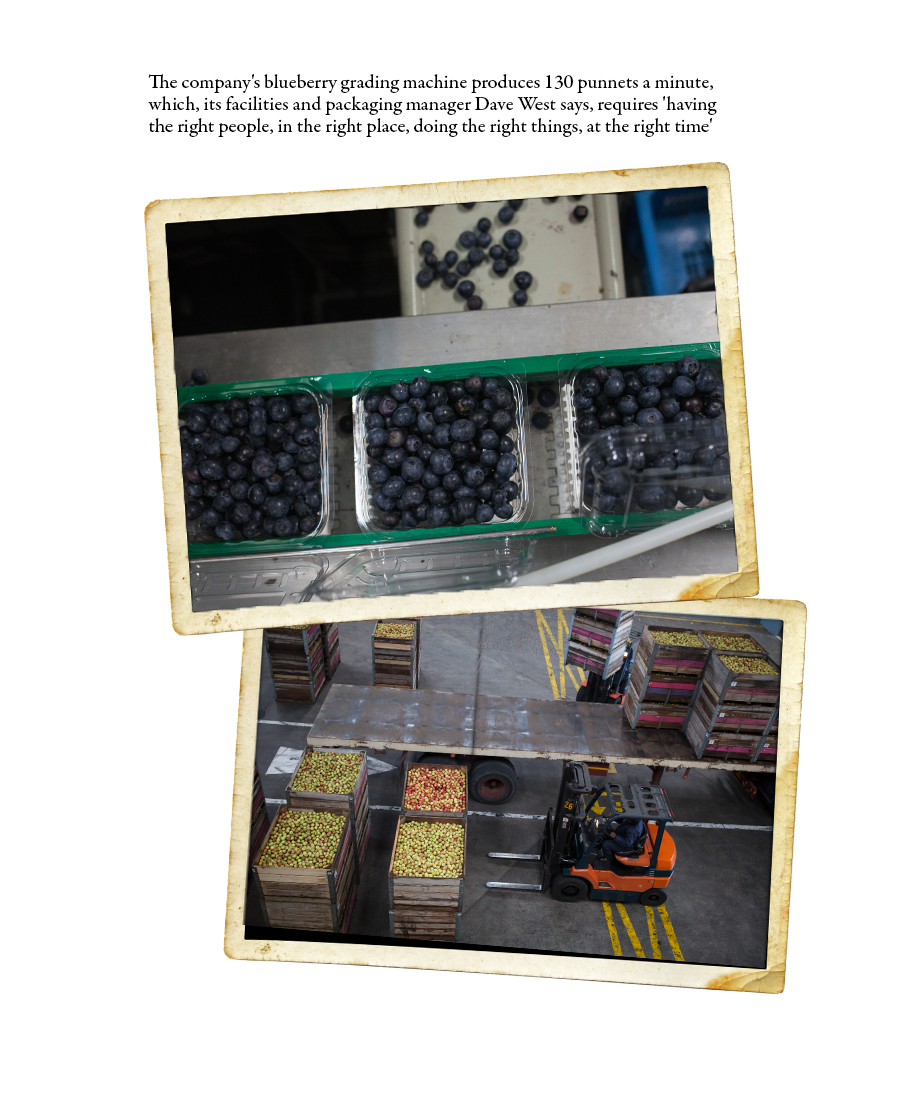

Blueberries are one of the factory’s biggest sellers. The speed and efficiency of the production line is a wonder to behold. A machine grades the blueberries, checking for size, defects, colour and stalks, before dropping weighed portions into punnets, which are sealed, coded and weighed again. If they are just one blueberry short, the pack is torn open and the berries reprocessed. The machine produces 130 punnets a minute, which are lifted off the conveyor belt, packed into green plastic trays and loaded on to wheeled dollies.

People and machines seem to work in harmony, and the pace is steady and fluid. “It’s about having the right people, in the right place, doing the right things, at the right time,” says facilities and packaging manager Dave West. “But it can get frantic. You have to meet lorry departure times, so if something arrives late, or there’s suddenly a bigger order, or a machine breaks down, you really feel the tension. But then it’s about how you react.” And the way they react is all hands to the pump. Managers roll up their sleeves – as did customers when staff were off sick during the Covid pandemic.

West and factory manager Rexine Burton are proud of their 99.98 per cent service levels (only 0.02 per cent of the one million weekly packs get rejected) and equally proud of their 111 employees, supplemented by 60 staff from their temp agency, CSP, which is co-located on the site. “We manage all our staff the same,” says Burton. KPIs are linked to quality, cost, morale and delivery, which are equally weighted and reviewed weekly. “Jobs are allocated on skillsets, and some people are better at some things than others – for example, you need momentum and skill to pack at the end of the line,” says regional HR director Richard Griffin, whose role is to coach, support and empower managers and team leaders, rather than working with employees directly. “But we are constantly helping people build their skills in a role and move them around to build their experience, so they can step up. We recruit externally [that is, outside the agency] only if we can’t fill internally, which helps build loyalty.”

Interaction between management and the factory floor is constant, not least through the employee forum. “And we encourage people to approach us directly – or their team leader or supervisor – if they want to discuss their progression,” says Burton. In 2023 the business has committed to making one significant site improvement every month in conjunction with the employee forum. Even the shift pattern, designed to give everyone a long weekend every fortnight and to ensure no one works more than three consecutive shifts, was decided jointly.

The factory’s success may depend on the right people being in the right place, at the right time, doing the right things, but this is a business based on trusting relationships and grounded in a service and knowledge culture – and as far from the traditional concept of Taylorism as it’s possible to be. Could their approach bear fruit in the wider economy? Burton and West certainly think so. “Dave and I often joke about this, but we’ve been saying for ages that people in the fresh produce industry, who have so many non-negotiable deadlines to meet – you just can’t short orders or miss vehicles – should move into a different area altogether, even the NHS. We’ve got so many organisational skills that we’ve learned over the years, I think we’d be great in that sort of environment.”

Multinational fresh produce company Dole’s UK factory sits on an unremarkable industrial estate just outside Spalding, among the flat fertile fields of south Lincolnshire. The sense of calm and order in the production area belies the complexity of the business, which operates 24 hours a day, 364 days a year, to move 254 product lines – from fine beans and baby corn to kale and kiwis, from drinking coconuts to M&S party food – in and out of the facility. Produce arrives from all over the world and Dole unpacks it, repacks it, ripens it, repacks it again, stores it and distributes it at a rate of around one million packs a week, to customers including major supermarkets and wholesalers.

Blueberries are one of the factory’s biggest sellers. The speed and efficiency of the production line is a wonder to behold. A machine grades the blueberries, checking for size, defects, colour and stalks, before dropping weighed portions into punnets, which are sealed, coded and weighed again. If they are just one blueberry short, the pack is torn open and the berries reprocessed. The machine produces 130 punnets a minute, which are lifted off the conveyor belt, packed into green plastic trays and loaded on to wheeled dollies.

People and machines seem to work in harmony, and the pace is steady and fluid. “It’s about having the right people, in the right place, doing the right things, at the right time,” says facilities and packaging manager Dave West. “But it can get frantic. You have to meet lorry departure times, so if something arrives late, or there’s suddenly a bigger order, or a machine breaks down, you really feel the tension. But then it’s about how you react.” And the way they react is all hands to the pump. Managers roll up their sleeves – as did customers when staff were off sick during the Covid pandemic.

West and factory manager Rexine Burton are proud of their 99.98 per cent service levels (only 0.02 per cent of the one million weekly packs get rejected) and equally proud of their 111 employees, supplemented by 60 staff from their temp agency, CSP, which is co-located on the site. “We manage all our staff the same,” says Burton. KPIs are linked to quality, cost, morale and delivery, which are equally weighted and reviewed weekly. “Jobs are allocated on skillsets, and some people are better at some things than others – for example, you need momentum and skill to pack at the end of the line,” says regional HR director Richard Griffin, whose role is to coach, support and empower managers and team leaders, rather than working with employees directly. “But we are constantly helping people build their skills in a role and move them around to build their experience, so they can step up. We recruit externally [that is, outside the agency] only if we can’t fill internally, which helps build loyalty.”

Interaction between management and the factory floor is constant, not least through the employee forum. “And we encourage people to approach us directly – or their team leader or supervisor – if they want to discuss their progression,” says Burton. In 2023 the business has committed to making one significant site improvement every month in conjunction with the employee forum. Even the shift pattern, designed to give everyone a long weekend every fortnight and to ensure no one works more than three consecutive shifts, was decided jointly.

The factory’s success may depend on the right people being in the right place, at the right time, doing the right things, but this is a business based on trusting relationships and grounded in a service and knowledge culture – and as far from the traditional concept of Taylorism as it’s possible to be. Could their approach bear fruit in the wider economy? Burton and West certainly think so. “Dave and I often joke about this, but we’ve been saying for ages that people in the fresh produce industry, who have so many non-negotiable deadlines to meet – you just can’t short orders or miss vehicles – should move into a different area altogether, even the NHS. We’ve got so many organisational skills that we’ve learned over the years, I think we’d be great in that sort of environment.”

Editor Jenny Roper

Art director Aubrey Smith

Freelance art editor Kayleigh Pavelin

Production editor Joanna Matthews

Picture editor Dominique Campbell

Editor in chief Robert Jeffery

Image credits

John Need; Frank Ramspott, Alubalish, Sean Gladwell, Monty Rakusen, Kelvin Murray, Erica Canepa/Bloomberg creative, Westend61/Getty Images