Premium access: CIPD Festival of Work 2024 | Digitally exclusive to content+

Work. Spring 2024, Issue 40

He had a seismic effect on online retail, was friends with presidents and popstars and spawned an almost fanatical HR following for his ideas on hierarchy.

Then he was found unresponsive on the dirty floor of a lean-to shed in Connecticut

The sudden, mysterious death of Zappos founder Tony Hsieh rocked the tech start-up world. So what happened? A highly individual case of addiction and poor mental health – or a cautionary tale of happiness as a corporate mission gone wrong?

Words Andrew Saunders

How does a famous entrepreneur who spent his life pursuing his own very distinct vision of happiness – not just for himself but for employees and others too – end up dying aged only 46 of smoke inhalation after spending the evening snorting laughing gas from whipped cream dispenser refill canisters? Not cocaine or heroin mind, the usual celeb drugs of choice – and not in some upscale hotel or exclusive mansion, either. But on the dirty floor of a lean-to shed attached to a weatherboard house in a small, unglamorous east coast American town.

It would be an ignominious end for anyone, never mind a former business guru whose company became a poster child for a new empowered generation of noughties employees. People for whom work was not merely a means to an end, but a place to have fun and an important source of happiness in their lives. Nevertheless, this is what happened to Tony Hsieh, best known as founder of offbeat online shoe retailer Zappos – whose wacky work culture and trend-setting championing of holacratic, non-hierarchical management was such a winner that he sold the business to Amazon for $1.2bn in 2009. He was also known as a social entrepreneur who tried his hand at everything from nightclubs and music festivals to urban regeneration – all of them united by the same mission of ‘delivering happiness to the world’.

On the evening of 18 November 2020, Hsieh was found unresponsive and lying on a filthy blanket by fire crew called to 500 Pequot Avenue, New London, Connecticut. He died nine days later in hospital, accompanied by a flurry of messages of condolence, from Bill Clinton and Jeff Bezos at one end of the celeb spectrum, to skateboarder Tony Hawk and even Ivanka Trump at the other. His fate is a tragic example of how outward success can mask inner turmoil, and how even those who achieve the universal modern dream of financial escape velocity can occasionally be brought crashing down to earth by their own demons. But it is also something of a cautionary tale for the career-minded. In an age when work and personal identities are so intertwined, should we be more wary of investing too much of ourselves in what we do or do not achieve in our careers? And with employers increasingly interested in the wellbeing of their employees, might the risks of encouraging happiness as an explicit workplace goal be greater than we think?

People who have ‘made it’ like Hsieh – he was worth in excess of $800bn at the time of his demise – are not supposed to die in the way he did, especially not in the US where the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are constitutionally enshrined. “How could someone of such great wealth who had spent his whole life touting the virtues of happiness and who was admired by people from all walks of life end up meeting such a tragic common man’s end?” asks David Jeans, co-author with Angel Au-Yeung of biography Wonder Boy: Tony Hsieh, Zappos and the Myth of Happiness in Silicon Valley.

Founded in 1999, Zappos looked like the culmination of a classic dotcom era success trajectory, and Hsieh himself a golden boy who could do no wrong. His first business – community-based online advertising start-up LinkExchange – had boomed so rapidly that he was able to sell to Microsoft for a cool $265m in 1998, only two years after founding it. The resulting cash, credibility and buzz enabled him not only to indulge in a few teenage dreams – he bought a nightclub and got into the rave scene – but also to go looking for a bigger career challenge. It was then he hit upon the idea for Zappos.

From the start Zappos did not follow the usual recipe. Footwear was not his passion – in fact Hsieh owned only a couple of pairs of sneakers and admitted he was “not that into shoes”. Despite his stellar track record, it was not VC funded (at least not to start with). And it was headquartered not in Silicon Valley where all the other hip, young tech start-ups hung out their shingles, but in gambling mecca Las Vegas – because Hsieh liked the party town atmosphere and he reasoned it would be easier to hire the friendly customer-facing employees he required there than in the tech-geek capital of California.

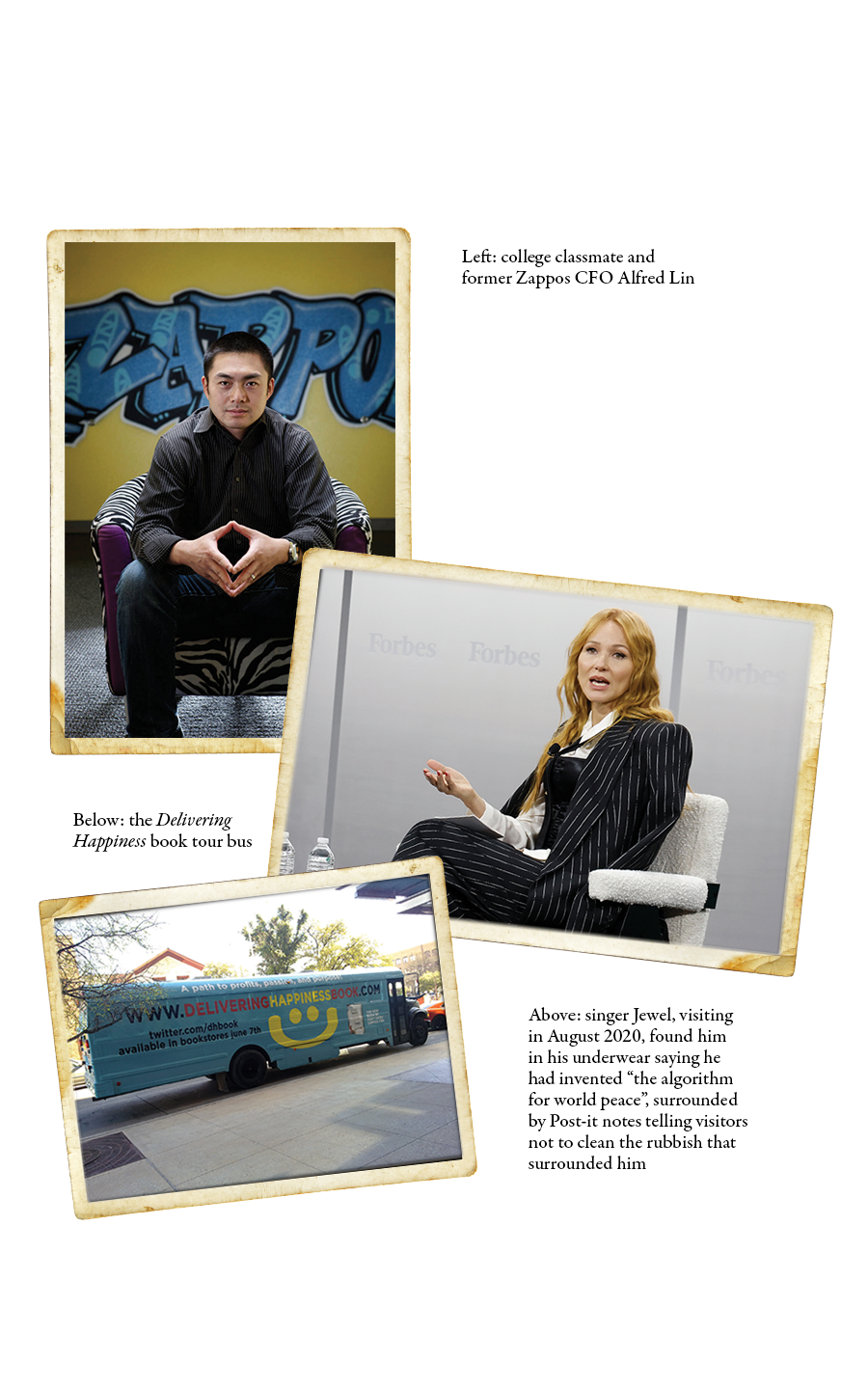

But if he was ambivalent about footwear he was absolutely determined to build a company that actively tried to boost the happiness of its employees. Zappos was what we might today call a ‘safe space’ where workers were encouraged not to don a suit of emotional armour every weekday and save getting their kicks for the weekend, but to bring their ‘whole selves’ to work instead. Visitors found vines hanging lushly from the ceiling and employees dressed up as dragons or unicorns scampering about the office. And far from being incentivised to do a certain number of calls an hour (as is usual call centre practice even today), those manning the phones at Zappos were encouraged to spend as long speaking to customers as the customers wanted them to – 10 hours and 43 minutes being the company’s claimed record for a single call.

His single-minded pursuit of a happy workplace was partly down to business acumen – happy employees were more likely to deliver great customer service – but also part of a bigger personal quest. The son of middle-class professional parents who emigrated from Taiwan to the US, Hsieh grew up in Marin County California – a posh neighbourhood with precious few other Asian Americans and where he was surrounded by much wealthier kids. His early life was dominated by the need to do well at school and live up to the ‘genius level’ intellect nature had gifted him. He only really came out of his shell at Harvard, where his dorm room became the late-night social hub for a group of like-minded souls. For the first time Hsieh found real personal fulfilment by creating a community – an MO that would follow him through the rest of his life. “He was never at ease as a child growing up in the environment that he did,” says Jeans. “At Harvard he first encountered joy and happiness, and from that moment on it seems like everything he did in his life was to try and recreate the feeling of that Harvard dorm room.”

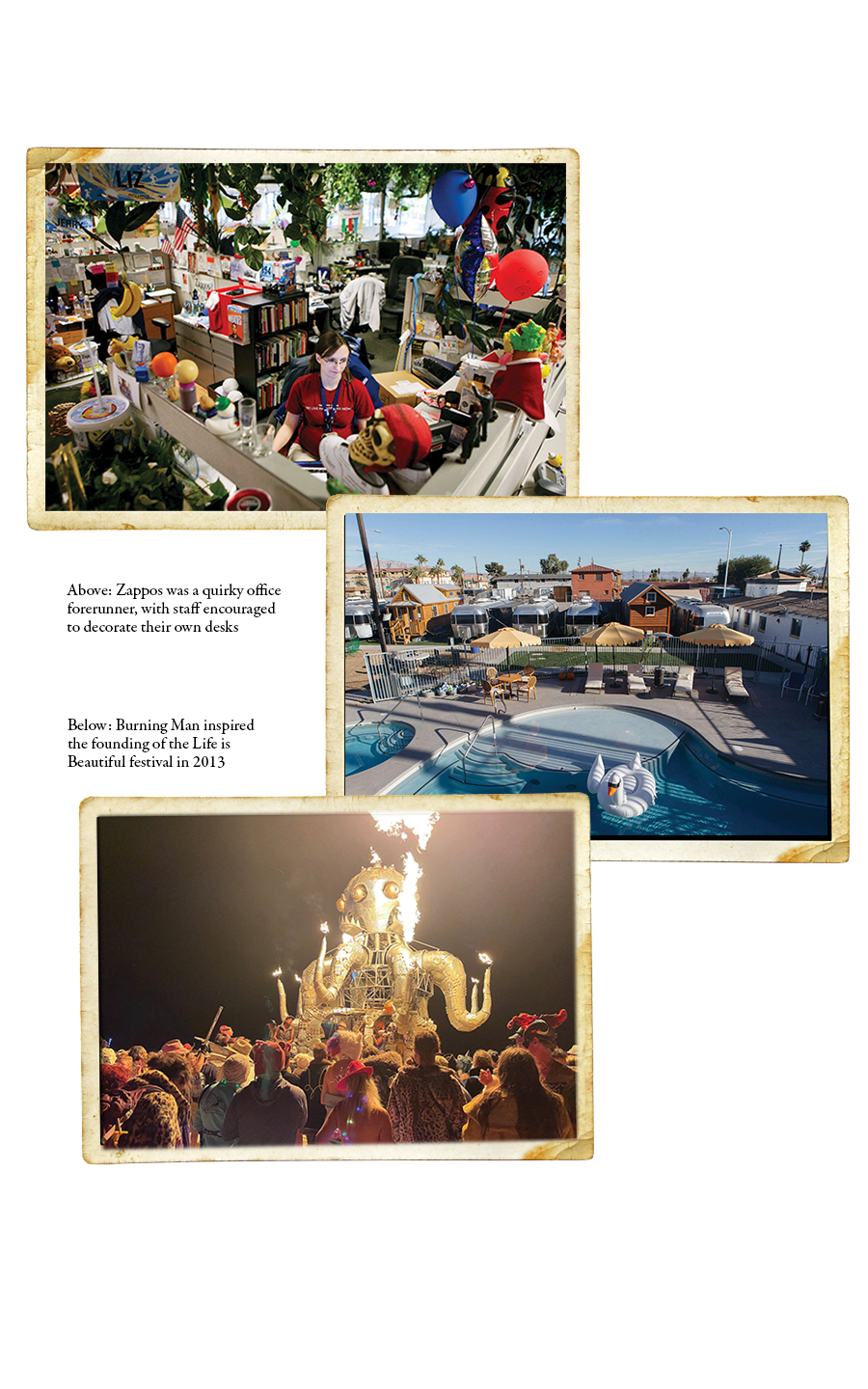

It is a lens that casts a revealing light on all his subsequent endeavours. Zappos became not only a fascinating business experiment but also a vehicle to provide its founder with a working environment he could flourish in. The Downtown Project – his ambitious plan to redevelop a deprived 60-acre swathe of the old centre of Las Vegas – went even further, attempting to project the dorm room vibe on to an entire city neighbourhood. The music festivals he loved – Burning Man, Life Is Beautiful – were another form of self-contained, instant community.

At Zappos he called himself ‘chief fungineer’ and would ask interviewees: on a scale of 1-10, how weird are you? explaining that those who answered with a low number were “probably a bit too straightlaced for us”. If they were successful, he would make them what came to be known as The Offer: as much as $5,000 cash not to take their new roles. Because anyone prepared to accept the bribe was unlikely to be sufficiently committed to do well at the company. It certainly helped to cement the culture that made Zappos the success it became. But it also enabled Hsieh to populate the company with the kind of people he liked to hang out with.

As idiosyncratic as some of these practices were, Zappos also caught something of the emerging happiness zeitgeist being championed by the likes of Semco CEO Ricardo Semler and economist Richard Florida at the time, prompting other entrepreneurs to follow suit. “His ideas were exciting and he built a fabulous company dedicated to customer service,” says Henry Stewart, founder and chief happiness officer at London-based tech training firm Happy Ltd, who cites Hsieh’s 2010 bestseller, Delivering Happiness, as one of his own inspirations to build a business based on happiness. “He used to say that people should ‘have fun and create a little weirdness’ at work. I love that: our own slogan at Happy is ‘creating joy in the workplace’.”

The Treehouse play area at Hsieh’s Downtown Project – a deprived corner of Las Vegas he spent $350m transforming

The Treehouse play area at Hsieh’s Downtown Project – a deprived corner of Las Vegas he spent $350m transforming

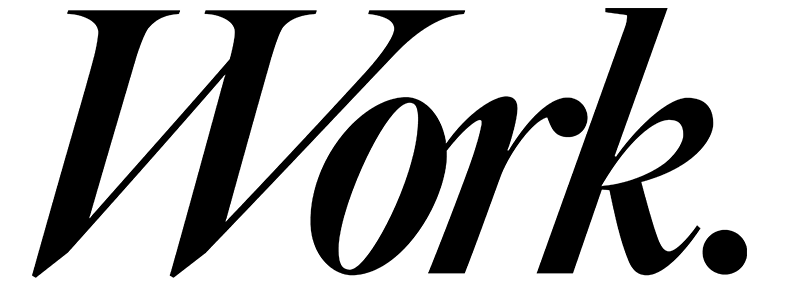

But behind the success and growing influence, cracks were already starting to show. Having discovered that alcohol helped him cope with persistent social anxiety, Hsieh had become a fairly heavy drinker and even adopted a suitably left-field signature tipple: the Italian digestivo Fernet-Branca, famed for its bitter taste and 39 per cent alcohol content. His long-time business partner Alfred Lin, the man who reined in some of Hsieh’s wilder excesses, quit Zappos in 2010. And he started to identify with his own myth a bit too closely – Delivering Happiness made it to the top of the bestseller list, but it did not get there without a bit of under the table help from its author, who used a third party to effectively buy a substantial number of copies of his own book.

Even the headline-making sale of Zappos to Amazon in 2009, which added around $214m to his net worth, may have accelerated his downward personal arc. Hsieh wrote subsequently that he did not want to sell, but the need to buy out some spooked investors who lost faith in his ‘social experiments’ during the 2008 crash meant he had little choice. It is certainly true that while he remained CEO until less than three months before his death, the gradual decline in his interest and involvement in Zappos can be traced back to the deal.

Of course it is not uncommon for ambitious business people to find that career success is not all it’s cracked up to be, points out veteran leadership coach Miranda Kennett. “I know several people who made it to CEO, the peak of their ambition, but it didn’t make them particularly happy.” For the more task and goal oriented, life at the top table can be much less enjoyable than they hoped, because the skills that got them there are not the ones that will make them a successful leader, she adds. “They may have very sharp elbows, then suddenly they are in a leadership position where they need other people not just to be compliant but to take the initiative and be committed.”

There are signs that Hsieh became increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of leadership, or at least with the responsibility it entails. In 2013 he started transitioning Zappos to the radical workplace decentralisation philosophy of holacracy, in which hierarchy and line managers are abolished and teams manage themselves instead. Touted as a way of keeping its employee-centric culture as the company grew, holacracy was not universally popular with ‘Zapponians’, many of whom left as a result. Decentralisation may give leaders more time to think great thoughts, but it has costs too. It can create frustration, fragment decision making and furnish opportunities for individuals to pursue their own agendas at the expense of others. In the last couple of years, the company has reportedly been reintroducing line managers and quietly dialling back on some other aspects of holacracy.

Comparisons between Hsieh and other high-profile entrepreneurs who have led rollercoaster lives are hard to avoid. One obvious candidate is mid 20th century movie mogul and airline owner Howard Hughes, whose story follows a similar arc – explosive success and apparent midas touch leading to personal isolation, paranoia and drug abuse. Hughes made it to 70 before he succumbed, however. More recently, WeWork founder Adam Neumann seems to have taken some leaves from the Tony Hsieh playbook; he built a business famed for its unconventional culture, had a favourite office tipple (Don Julio tequila at $140 a bottle) and reportedly smoked so much weed on his private jet that the crew had to wear oxygen masks. But – even if he was ousted from his own business after it lost 90 per cent of its $47bn valuation – Neumann is still very much alive and kicking, and now apparently trying to buy WeWork back out of bankruptcy.

Hsieh’s drug use was, however, a lot more than merely recreational. Ironically as part of a search for ‘healthier’ ways of managing his social anxiety than alcohol, he not only took to nitrous oxide – ‘hippy crack’ as it is sometimes called – but also turned to horse tranquiliser ketamine, known for its dissociative effects on users. Not a great choice for a man who, while he revelled in a sense of community, paradoxically found making close one-to-one relationships difficult. That was when things started to “fall off the cliff edge”, says Jeans. Like many an in-denial drug addict before him, Hsieh apparently believed he could control the drugs rather than the drugs controlling him. “He had built a billion-dollar business, sold it to Amazon and was struggling to find what his next thing was going to be. His discovery of ketamine really led him to a place where he was incredibly unwell.”

Unveiled in December 2023, a new mural at Strong Start Academy Elementary School in downtown Las Vegas celebrated – along with a bronze bust – what would have been Hsieh’s 50th birthday

Unveiled in December 2023, a new mural at Strong Start Academy Elementary School in downtown Las Vegas celebrated – along with a bronze bust – what would have been Hsieh’s 50th birthday

Of course the pursuit of happiness does not always lead down a K hole. But while it seems self evident that it is better for people to be happy rather than unhappy at work, attempts by employers to actively ‘make’ their employees happier will not necessarily bear fruit, says André Spicer, professor of organisational behaviour and executive dean at Bayes Business School: “The idea that people should be happy at work is a reasonable goal. But the way in which we go about it can be counterproductive and undermine the stated intent.”

Take the post-pandemic preoccupation with mental health and wellbeing. A study published in January of 46,000 UK workers by William Fleming at the Wellbeing Research Centre at Oxford University found no evidence that a whole range of popular interventions such as mindfulness, resilience and stress reduction classes and apps have any appreciable impact on mental health at work. What does make a difference? A reasonable workload and decent working hours for a start, but the biggest single improvement noted in the report “was actually employee voice”, says Spicer: “People feeling like they have a voice in the workplace, that they can speak up and they will be listened to.”

Hsieh certainly did more than speak up for the residents of downtown Las Vegas, where his attention was increasingly focused from 2012. He committed $350m of his personal fortune to an ambitious urban redevelopment programme aimed at creating another new community – that word again – this time seeded by start-up businesses that would be bankrolled by Hsieh. Replacing dive bars and strip joints with coffee shops, offices and artisan juice emporiums required vision, which he had aplenty. But it also took commitment, which by then he seemed to be running short of.

Despite being the architect and financier of the scheme to turn the deprived centre of town into a kind of Silicon Valley-style incubator for happiness, Hsieh only seemed increasingly unwilling to be held accountable when things at the Downtown Project didn’t go well. Following the suicides of three entrepreneurs involved in the scheme over two years, he first tried to distance himself with a statement, saying: “I have never described myself as the CEO of the Downtown Project” before apparently realising that CEO was what people in the town saw him as regardless, and formally stepping down as leader in 2014. “Building a neighbourhood is very different to building a business,” says Jeans. “Expecting everyone in a community to be happy doesn’t leave much room for the reality of other emotions, such as the sadness everyone felt after the suicides that occurred.”

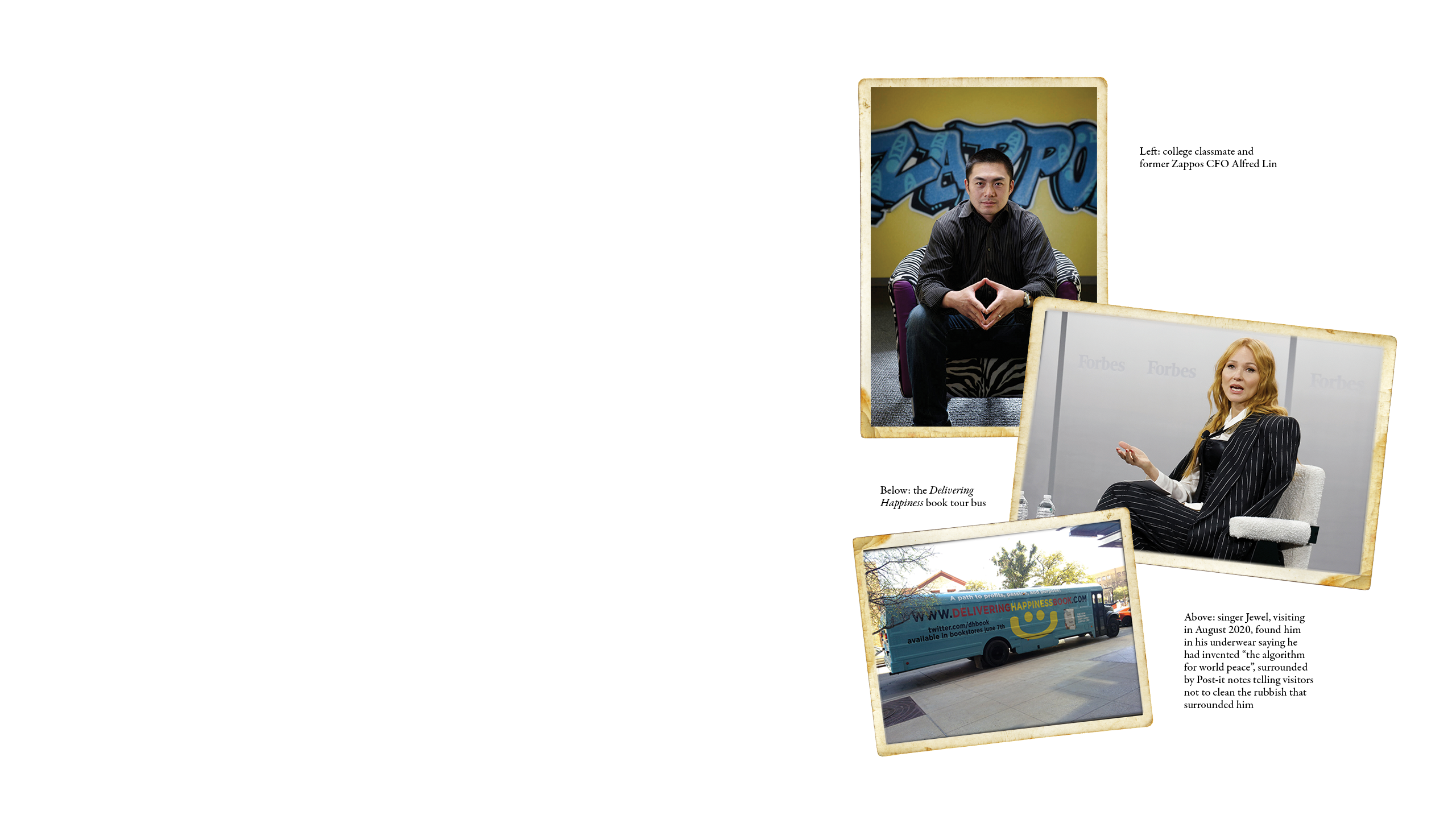

By then taking a reported five grams of ketamine a day as well as constantly snorting laughing gas because he believed it would eliminate the need for sleep, he retreated to a trailer park he called Airstream Park. He lived there in a mobile home with two alpacas, telling Business Insider in August 2020 that he did so because he “wanted to maximise serendipity and randomness in my life”. It was at about this point that singer Jewel – who had met Hsieh in happier times on a trip to celebrity haunt Necker Island – paid her old friend a visit. She was shocked by the state he was living in, surrounded by rotten food and with dog faeces on the floor, and also by the hanger-on ‘employees’ who seemed to facilitate his downward spiral rather than trying to help him out of it. After failing to impinge the danger she felt he was in on him face to face, she wrote a letter that would come to have a tragic resonance following his death a few months later. “You are in trouble, Tony,” she wrote. “I need to tell you that you are taking too many drugs that cause you to dissociate... the people you are surrounding yourself with are either ignorant or willing to be complicit in your killing yourself... I don’t think this is your time to die... I say this with love, and as possibly the only person in your circle who is not on your payroll.”

He did not get off the destructive path he was on. Perhaps by then it was already too late. Hsieh’s personal quest for happiness failed, and there are certainly aspects of his life that are far from admirable. But his wider legacy is surely more positive. Many successful entrepreneurs got their first break thanks to him. Lots of employers are now at least thinking about what they can do to make the workplace happier, even if they haven’t got all the answers just yet. And he made a bold and energetic stand against ‘business as usual’ capitalism in an era when that was far from the norm. He deserves to be remembered for more than the inglorious and headline-grabbing manner of his passing, concludes Jeans. “When people think of Tony today, they mainly remember a man who really did try to disrupt corporate culture and prove that a focus on the happiness of employees could turn into profits. That’s a refreshing and remarkable way to run a company.”

How does a famous entrepreneur who spent his life pursuing his own very distinct vision of happiness – not just for himself but for employees and others too – end up dying aged only 46 of smoke inhalation after spending the evening snorting laughing gas from whipped cream dispenser refill canisters? Not cocaine or heroin mind, the usual celeb drugs of choice – and not in some upscale hotel or exclusive mansion, either. But on the dirty floor of a lean-to shed attached to a weatherboard house in a small, unglamorous east coast American town.

It would be an ignominious end for anyone, never mind a former business guru whose company became a poster child for a new empowered generation of noughties employees. People for whom work was not merely a means to an end, but a place to have fun and an important source of happiness in their lives. Nevertheless, this is what happened to Tony Hsieh, best known as founder of offbeat online shoe retailer Zappos – whose wacky work culture and trend-setting championing of holacratic, non-hierarchical management was such a winner that he sold the business to Amazon for $1.2bn in 2009. He was also known as a social entrepreneur who tried his hand at everything from nightclubs and music festivals to urban regeneration – all of them united by the same mission of ‘delivering happiness to the world’.

On the evening of 18 November 2020, Hsieh was found unresponsive and lying on a filthy blanket by fire crew called to 500 Pequot Avenue, New London, Connecticut. He died nine days later in hospital, accompanied by a flurry of messages of condolence, from Bill Clinton and Jeff Bezos at one end of the celeb spectrum, to skateboarder Tony Hawk and even Ivanka Trump at the other. His fate is a tragic example of how outward success can mask inner turmoil, and how even those who achieve the universal modern dream of financial escape velocity can occasionally be brought crashing down to earth by their own demons. But it is also something of a cautionary tale for the career-minded. In an age when work and personal identities are so intertwined, should we be more wary of investing too much of ourselves in what we do or do not achieve in our careers? And with employers increasingly interested in the wellbeing of their employees, might the risks of encouraging happiness as an explicit workplace goal be greater than we think?

People who have ‘made it’ like Hsieh – he was worth in excess of $800bn at the time of his demise – are not supposed to die in the way he did, especially not in the US where the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness are constitutionally enshrined. “How could someone of such great wealth who had spent his whole life touting the virtues of happiness and who was admired by people from all walks of life end up meeting such a tragic common man’s end?” asks David Jeans, co-author with Angel Au-Yeung of biography Wonder Boy: Tony Hsieh, Zappos and the Myth of Happiness in Silicon Valley.

Founded in 1999, Zappos looked like the culmination of a classic dotcom era success trajectory, and Hsieh himself a golden boy who could do no wrong. His first business – community-based online advertising start-up LinkExchange – had boomed so rapidly that he was able to sell to Microsoft for a cool $265m in 1998, only two years after founding it. The resulting cash, credibility and buzz enabled him not only to indulge in a few teenage dreams – he bought a nightclub and got into the rave scene – but also to go looking for a bigger career challenge. It was then he hit upon the idea for Zappos.

From the start Zappos did not follow the usual recipe. Footwear was not his passion – in fact Hsieh owned only a couple of pairs of sneakers and admitted he was “not that into shoes”. Despite his stellar track record, it was not VC funded (at least not to start with). And it was headquartered not in Silicon Valley where all the other hip, young tech start-ups hung out their shingles, but in gambling mecca Las Vegas – because Hsieh liked the party town atmosphere and he reasoned it would be easier to hire the friendly customer-facing employees he required there than in the tech-geek capital of California.

But if he was ambivalent about footwear he was absolutely determined to build a company that actively tried to boost the happiness of its employees. Zappos was what we might today call a ‘safe space’ where workers were encouraged not to don a suit of emotional armour every weekday and save getting their kicks for the weekend, but to bring their ‘whole selves’ to work instead. Visitors found vines hanging lushly from the ceiling and employees dressed up as dragons or unicorns scampering about the office. And far from being incentivised to do a certain number of calls an hour (as is usual call centre practice even today), those manning the phones at Zappos were encouraged to spend as long speaking to customers as the customers wanted them to – 10 hours and 43 minutes being the company’s claimed record for a single call.

His single-minded pursuit of a happy workplace was partly down to business acumen – happy employees were more likely to deliver great customer service – but also part of a bigger personal quest. The son of middle-class professional parents who emigrated from Taiwan to the US, Hsieh grew up in Marin County California – a posh neighbourhood with precious few other Asian Americans and where he was surrounded by much wealthier kids. His early life was dominated by the need to do well at school and live up to the ‘genius level’ intellect nature had gifted him. He only really came out of his shell at Harvard, where his dorm room became the late-night social hub for a group of like-minded souls. For the first time Hsieh found real personal fulfilment by creating a community – an MO that would follow him through the rest of his life. “He was never at ease as a child growing up in the environment that he did,” says Jeans. “At Harvard he first encountered joy and happiness, and from that moment on it seems like everything he did in his life was to try and recreate the feeling of that Harvard dorm room.”

It is a lens that casts a revealing light on all his subsequent endeavours. Zappos became not only a fascinating business experiment but also a vehicle to provide its founder with a working environment he could flourish in. The Downtown Project – his ambitious plan to redevelop a deprived 60-acre swathe of the old centre of Las Vegas – went even further, attempting to project the dorm room vibe on to an entire city neighbourhood. The music festivals he loved – Burning Man, Life Is Beautiful – were another form of self-contained, instant community.

At Zappos he called himself ‘chief fungineer’ and would ask interviewees: on a scale of 1-10, how weird are you? explaining that those who answered with a low number were “probably a bit too straightlaced for us”. If they were successful, he would make them what came to be known as The Offer: as much as $5,000 cash not to take their new roles. Because anyone prepared to accept the bribe was unlikely to be sufficiently committed to do well at the company. It certainly helped to cement the culture that made Zappos the success it became. But it also enabled Hsieh to populate the company with the kind of people he liked to hang out with.

As idiosyncratic as some of these practices were, Zappos also caught something of the emerging happiness zeitgeist being championed by the likes of Semco CEO Ricardo Semler and economist Richard Florida at the time, prompting other entrepreneurs to follow suit. “His ideas were exciting and he built a fabulous company dedicated to customer service,” says Henry Stewart, founder and chief happiness officer at London-based tech training firm Happy Ltd, who cites Hsieh’s 2010 bestseller, Delivering Happiness, as one of his own inspirations to build a business based on happiness. “He used to say that people should ‘have fun and create a little weirdness’ at work. I love that: our own slogan at Happy is ‘creating joy in the workplace’.”

The Treehouse play area at Hsieh’s Downtown Project – a deprived corner of Las Vegas he spent $350m transforming

The Treehouse play area at Hsieh’s Downtown Project – a deprived corner of Las Vegas he spent $350m transforming

But behind the success and growing influence, cracks were already starting to show. Having discovered that alcohol helped him cope with persistent social anxiety, Hsieh had become a fairly heavy drinker and even adopted a suitably left-field signature tipple: the Italian digestivo Fernet-Branca, famed for its bitter taste and 39 per cent alcohol content. His long-time business partner Alfred Lin, the man who reined in some of Hsieh’s wilder excesses, quit Zappos in 2010. And he started to identify with his own myth a bit too closely – Delivering Happiness made it to the top of the bestseller list, but it did not get there without a bit of under the table help from its author, who used a third party to effectively buy a substantial number of copies of his own book.

Even the headline-making sale of Zappos to Amazon in 2009, which added around $214m to his net worth, may have accelerated his downward personal arc. Hsieh wrote subsequently that he did not want to sell, but the need to buy out some spooked investors who lost faith in his ‘social experiments’ during the 2008 crash meant he had little choice. It is certainly true that while he remained CEO until less than three months before his death, the gradual decline in his interest and involvement in Zappos can be traced back to the deal.

Of course it is not uncommon for ambitious business people to find that career success is not all it’s cracked up to be, points out veteran leadership coach Miranda Kennett. “I know several people who made it to CEO, the peak of their ambition, but it didn’t make them particularly happy.” For the more task and goal oriented, life at the top table can be much less enjoyable than they hoped, because the skills that got them there are not the ones that will make them a successful leader, she adds. “They may have very sharp elbows, then suddenly they are in a leadership position where they need other people not just to be compliant but to take the initiative and be committed.”

There are signs that Hsieh became increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of leadership, or at least with the responsibility it entails. In 2013 he started transitioning Zappos to the radical workplace decentralisation philosophy of holacracy, in which hierarchy and line managers are abolished and teams manage themselves instead. Touted as a way of keeping its employee-centric culture as the company grew, holacracy was not universally popular with ‘Zapponians’, many of whom left as a result. Decentralisation may give leaders more time to think great thoughts, but it has costs too. It can create frustration, fragment decision making and furnish opportunities for individuals to pursue their own agendas at the expense of others. In the last couple of years, the company has reportedly been reintroducing line managers and quietly dialling back on some other aspects of holacracy.

Comparisons between Hsieh and other high-profile entrepreneurs who have led rollercoaster lives are hard to avoid. One obvious candidate is mid 20th century movie mogul and airline owner Howard Hughes, whose story follows a similar arc – explosive success and apparent midas touch leading to personal isolation, paranoia and drug abuse. Hughes made it to 70 before he succumbed, however. More recently, WeWork founder Adam Neumann seems to have taken some leaves from the Tony Hsieh playbook; he built a business famed for its unconventional culture, had a favourite office tipple (Don Julio tequila at $140 a bottle) and reportedly smoked so much weed on his private jet that the crew had to wear oxygen masks. But – even if he was ousted from his own business after it lost 90 per cent of its $47bn valuation – Neumann is still very much alive and kicking, and now apparently trying to buy WeWork back out of bankruptcy.

Hsieh’s drug use was, however, a lot more than merely recreational. Ironically as part of a search for ‘healthier’ ways of managing his social anxiety than alcohol, he not only took to nitrous oxide – ‘hippy crack’ as it is sometimes called – but also turned to horse tranquiliser ketamine, known for its dissociative effects on users. Not a great choice for a man who, while he revelled in a sense of community, paradoxically found making close one-to-one relationships difficult. That was when things started to “fall off the cliff edge”, says Jeans. Like many an in-denial drug addict before him, Hsieh apparently believed he could control the drugs rather than the drugs controlling him. “He had built a billion-dollar business, sold it to Amazon and was struggling to find what his next thing was going to be. His discovery of ketamine really led him to a place where he was incredibly unwell.”

Unveiled in December 2023, a new mural at Strong Start Academy Elementary School in downtown Las Vegas celebrated – along with a bronze bust – what would have been Hsieh’s 50th birthday

Unveiled in December 2023, a new mural at Strong Start Academy Elementary School in downtown Las Vegas celebrated – along with a bronze bust – what would have been Hsieh’s 50th birthday

Of course the pursuit of happiness does not always lead down a K hole. But while it seems self evident that it is better for people to be happy rather than unhappy at work, attempts by employers to actively ‘make’ their employees happier will not necessarily bear fruit, says André Spicer, professor of organisational behaviour and executive dean at Bayes Business School: “The idea that people should be happy at work is a reasonable goal. But the way in which we go about it can be counterproductive and undermine the stated intent.”

Take the post-pandemic preoccupation with mental health and wellbeing. A study published in January of 46,000 UK workers by William Fleming at the Wellbeing Research Centre at Oxford University found no evidence that a whole range of popular interventions such as mindfulness, resilience and stress reduction classes and apps have any appreciable impact on mental health at work. What does make a difference? A reasonable workload and decent working hours for a start, but the biggest single improvement noted in the report “was actually employee voice”, says Spicer: “People feeling like they have a voice in the workplace, that they can speak up and they will be listened to.”

Hsieh certainly did more than speak up for the residents of downtown Las Vegas, where his attention was increasingly focused from 2012. He committed $350m of his personal fortune to an ambitious urban redevelopment programme aimed at creating another new community – that word again – this time seeded by start-up businesses that would be bankrolled by Hsieh. Replacing dive bars and strip joints with coffee shops, offices and artisan juice emporiums required vision, which he had aplenty. But it also took commitment, which by then he seemed to be running short of.

Despite being the architect and financier of the scheme to turn the deprived centre of town into a kind of Silicon Valley-style incubator for happiness, Hsieh only seemed increasingly unwilling to be held accountable when things at the Downtown Project didn’t go well. Following the suicides of three entrepreneurs involved in the scheme over two years, he first tried to distance himself with a statement, saying: “I have never described myself as the CEO of the Downtown Project” before apparently realising that CEO was what people in the town saw him as regardless, and formally stepping down as leader in 2014. “Building a neighbourhood is very different to building a business,” says Jeans. “Expecting everyone in a community to be happy doesn’t leave much room for the reality of other emotions, such as the sadness everyone felt after the suicides that occurred.”

By then taking a reported five grams of ketamine a day as well as constantly snorting laughing gas because he believed it would eliminate the need for sleep, he retreated to a trailer park he called Airstream Park. He lived there in a mobile home with two alpacas, telling Business Insider in August 2020 that he did so because he “wanted to maximise serendipity and randomness in my life”. It was at about this point that singer Jewel – who had met Hsieh in happier times on a trip to celebrity haunt Necker Island – paid her old friend a visit. She was shocked by the state he was living in, surrounded by rotten food and with dog faeces on the floor, and also by the hanger-on ‘employees’ who seemed to facilitate his downward spiral rather than trying to help him out of it. After failing to impinge the danger she felt he was in on him face to face, she wrote a letter that would come to have a tragic resonance following his death a few months later. “You are in trouble, Tony,” she wrote. “I need to tell you that you are taking too many drugs that cause you to dissociate... the people you are surrounding yourself with are either ignorant or willing to be complicit in your killing yourself... I don’t think this is your time to die... I say this with love, and as possibly the only person in your circle who is not on your payroll.”

He did not get off the destructive path he was on. Perhaps by then it was already too late. Hsieh’s personal quest for happiness failed, and there are certainly aspects of his life that are far from admirable. But his wider legacy is surely more positive. Many successful entrepreneurs got their first break thanks to him. Lots of employers are now at least thinking about what they can do to make the workplace happier, even if they haven’t got all the answers just yet. And he made a bold and energetic stand against ‘business as usual’ capitalism in an era when that was far from the norm. He deserves to be remembered for more than the inglorious and headline-grabbing manner of his passing, concludes Jeans. “When people think of Tony today, they mainly remember a man who really did try to disrupt corporate culture and prove that a focus on the happiness of employees could turn into profits. That’s a refreshing and remarkable way to run a company.”

One of dozens of installations forming thebackdrop to Hsieh's Life is Beautiful festoval. English artist D*Face's mural struck a chord with champions of this long-overlookeds area. D*Face - www.dface.co.uk @Dface_offical

One of dozens of installations forming thebackdrop to Hsieh's Life is Beautiful festoval. English artist D*Face's mural struck a chord with champions of this long-overlookeds area. D*Face - www.dface.co.uk @Dface_offical

Editor Jenny Roper

Art director Aubrey Smith

Freelance art editor Kayleigh Pavelin

Production editor Joanna Matthews

Picture editor Dominique Campbell

Editor in chief Robert Jeffery

Image credits

FilmMagic, Taylor Hill, Ronda Churchill/Bloomberg, Julie Jammot/AFP, Alubalish, Jason Ogulnik for The Washington Post, Mike Windle for Vanity Fair/Getty Images; Cavan Images, Mikayla Whitmore/Las Vegas Sun/Associated Press, AP Photo/Brennan Linsley, New London Fire Department/AP/Alamy Stock Photo; C.C. Chapman; Courtesy of the City of Las Vegas