Premium access: CIPD Festival of Work 2024 | Digitally exclusive to content+

Work. Spring 2024, Issue 40

Strategy eats culture for breakfast.

|

Discuss

Is company culture more nebulous, more organically formed, than management gurus and CEOs often have it? And does our ‘how we do things around here’ obsession risks eclipsing stuff HR might actually control?

Words Katie Jacobs

In the mid-1950s, renowned business theorist and psychologist Edgar Schein served in the US army. The Korean War had recently ended and Schein spent time interviewing American prisoners of war about their experiences of Chinese indoctrination attempts. Reflecting on his experiences in a 2012 interview, Schein discussed the concept of ‘coercive persuasion’ (a term he coined) and how he later discovered that it applied as much to organisations as to a Communist army: “If I have you physically captured, I can influence you if I choose to,” he said. “It applies to the POWs, but it applies equally to golden handcuffs. If I’m economically committed to an institution… I am going to allow myself – or be forced – to be socialised into their culture.”

The context – prisoner of war camp versus modern organisation – might, we hope at least, be very different. But as Schein, who began focusing on organisations after leaving military service and remained a respected commentator for the rest of his long career (he died in 2023 aged 94), himself pointed out, there are parallels for how we think about the potential impacts, good and bad, of corporate culture.

Fast forward to 2024 and business culture has never been a hotter topic. To comply with the (non-legally binding) Corporate Governance Code, the boards of UK listed companies are now – as of 2018 – asked to “assess and monitor culture and how the desired culture has been embedded”. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) keeps a close eye on financial services institutions, expecting “senior leaders to nurture healthy cultures in the firms they lead”. Business leaders extol having the right culture as a source of competitive advantage, and there is no shortage of headlines exposing the harmful impacts of a toxic culture, everywhere from the Met Police to the CBI.

For senior HR leaders, it is a space where they are spending an increasing amount of time and energy, with stakeholder interest raising the profile of people and organisational issues under the amorphous label ‘culture’. Quite a few HR directors have even rebranded themselves chief people and culture officers. But is culture actually as important as we like to think it is to organisational success (or failure)? Is it, indeed, the most important thing as many believe? Or is it worth asking whether the HR and business community has been co-opted into something of a ‘culture cult’, focusing myopically on what is at best an intangible concept? These are provocative questions given how critical many leaders believe (or say they believe) culture to be. But if we cannot accurately define and measure culture – not that many haven’t tried or would not willingly sell you a tool that claims to be able to do so – do we risk getting distracted from other, more material organisational issues?

Blackbird © American Society for Microbiology

Blackbird © American Society for Microbiology

Blackbird © American Society for Microbiology

Blackbird © American Society for Microbiology

In the mid-1950s, renowned business theorist and psychologist Edgar Schein served in the US army. The Korean War had recently ended and Schein spent time interviewing American prisoners of war about their experiences of Chinese indoctrination attempts. Reflecting on his experiences in a 2012 interview, Schein discussed the concept of ‘coercive persuasion’ (a term he coined) and how he later discovered that it applied as much to organisations as to a Communist army: “If I have you physically captured, I can influence you if I choose to,” he said. “It applies to the POWs, but it applies equally to golden handcuffs. If I’m economically committed to an institution… I am going to allow myself – or be forced – to be socialised into their culture.”

The context – prisoner of war camp versus modern organisation – might, we hope at least, be very different. But as Schein, who began focusing on organisations after leaving military service and remained a respected commentator for the rest of his long career (he died in 2023 aged 94), himself pointed out, there are parallels for how we think about the potential impacts, good and bad, of corporate culture.

Fast forward to 2024 and business culture has never been a hotter topic. To comply with the (non-legally binding) Corporate Governance Code, the boards of UK listed companies are now – as of 2018 – asked to “assess and monitor culture and how the desired culture has been embedded”. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) keeps a close eye on financial services institutions, expecting “senior leaders to nurture healthy cultures in the firms they lead”. Business leaders extol having the right culture as a source of competitive advantage, and there is no shortage of headlines exposing the harmful impacts of a toxic culture, everywhere from the Met Police to the CBI.

For senior HR leaders, it is a space where they are spending an increasing amount of time and energy, with stakeholder interest raising the profile of people and organisational issues under the amorphous label ‘culture’. Quite a few HR directors have even rebranded themselves chief people and culture officers. But is culture actually as important as we like to think it is to organisational success (or failure)? Is it, indeed, the most important thing as many believe? Or is it worth asking whether the HR and business community has been co-opted into something of a ‘culture cult’, focusing myopically on what is at best an intangible concept? These are provocative questions given how critical many leaders believe (or say they believe) culture to be. But if we cannot accurately define and measure culture – not that many haven’t tried or would not willingly sell you a tool that claims to be able to do so – do we risk getting distracted from other, more material organisational issues?

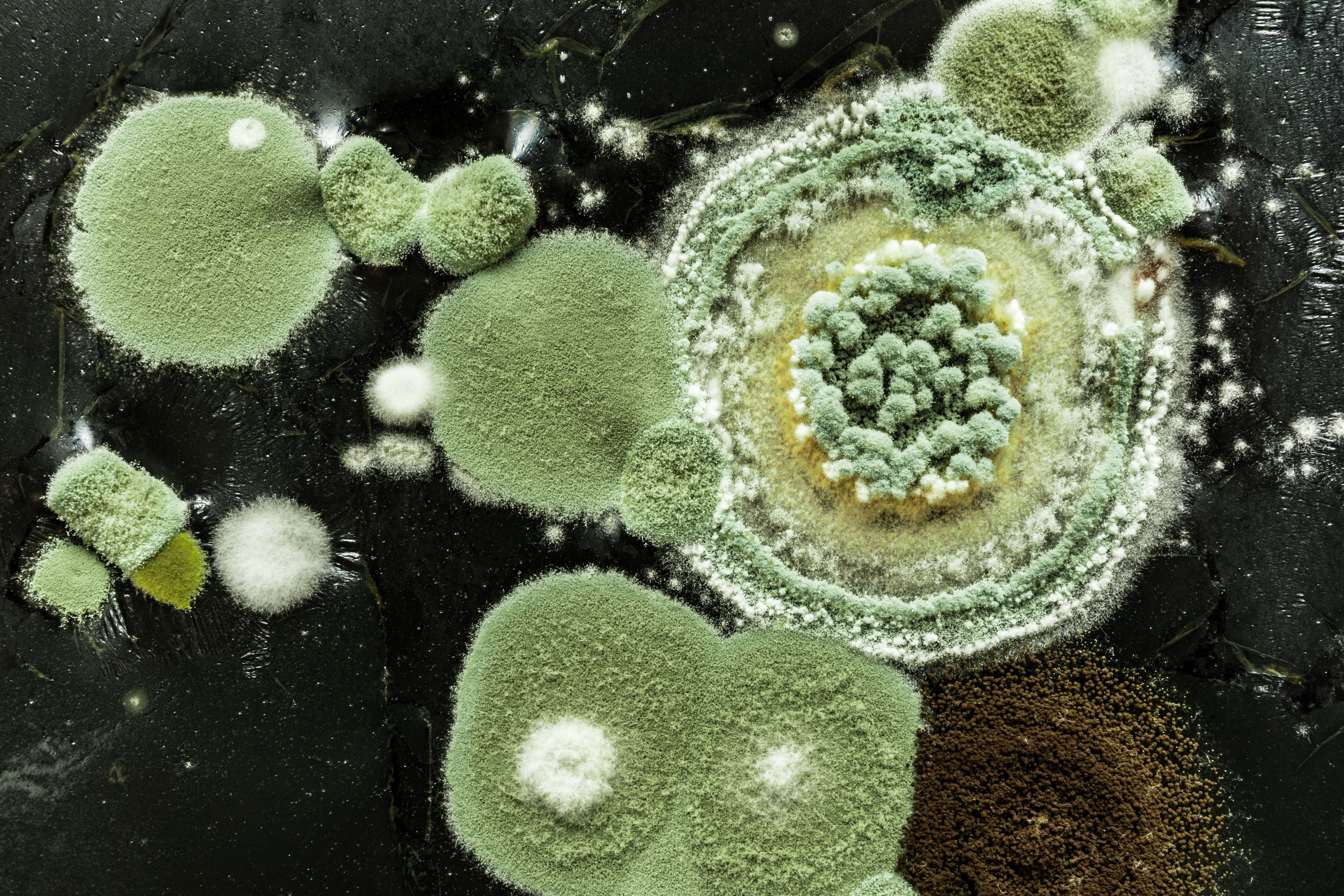

Creating artworks by culturing micro-organisms – bacteria, yeast, fungi or protists – is a bit like painting. But because the hues are living cells, it is hard to control exactly what they will do – much like organisational culture, you might say. For artists trying to configure very specific images (astronauts, goldfish, Vincent van Gogh…) this can be irksome. For others – as with these shortlisted entries to last year’s Agar Art Contest – there is a delicate balance between nudging the microbes and allowing unexpected, beautiful abstractions to unfold | Day of Science, 2023 Agar Art © American Society for Microbiology

Creating artworks by culturing micro-organisms – bacteria, yeast, fungi or protists – is a bit like painting. But because the hues are living cells, it is hard to control exactly what they will do – much like organisational culture, you might say. For artists trying to configure very specific images (astronauts, goldfish, Vincent van Gogh…) this can be irksome. For others – as with these shortlisted entries to last year’s Agar Art Contest – there is a delicate balance between nudging the microbes and allowing unexpected, beautiful abstractions to unfold | Day of Science, 2023 Agar Art © American Society for Microbiology

Outer space by artist Nisanur Meral © American Society for Microbiology

Outer space by artist Nisanur Meral © American Society for Microbiology

To ascertain whether culture really eats strategy for breakfast (as management guru Peter Drucker had it), it is first worth diving into its history. While Schein is one of the most influential early names in organisational culture, it was Canadian psychoanalyst and social scientist Elliott Jacques who came up with the commonly used definition of culture as ‘the way we do things around here’, extending culture beyond its more traditional anthropological meaning. Jacques (who also coined the term ‘midlife crisis’) observed the culture within a London ball-bearing factory over three years, publishing The Changing Culture of a Factory in 1951.

But it was not until the 1980s that culture became seen as something for business leaders to pay attention to and attempt to manipulate, says André Spicer, professor of organisational behaviour at Bayes Business School. “Companies had been trying to change culture for years, but an explicit focus on corporate culture came out of the 1980s, largely driven by the ‘Japanese threat’,” he explains. That led to an obsession with replicating corporate Japan’s ‘quality’ culture, which then morphed into a focus on innovation during the late 1990s’ dotcom bubble. The global financial crisis brought sharp attention to the damaging impact of high-risk and unethical cultures – “getting the culture right to stop people doing wrong things”, as Spicer puts it. And it led to the introduction of more oversight and regulation. Today, discussion is often tied to the post-pandemic return to the office, with concern over the impact of long-term remote working on corporate culture.

What still remains somewhat woolly is how we define culture – everyone might be talking about it, but the chances are we are all talking about slightly different things. As a CIPD paper exploring the difference between culture and climate reads: “The problem with the concept of organisational culture is not that it lacks meaning, but that it has too many meanings.” In fact there are more than 50 distinct definitions in academic literature. Ask a business or HR leader and it is likely they will quote Jacques. But Spicer rates Schein’s description of culture as ‘an iceberg’ – with visible artefacts at the top and harder to define or understand values and assumptions lying beneath the water’s surface – as the best. (Schein also proposed that organisational culture is passed on or taught to people as “the correct way to perceive, think and feel”, something that could sound rather sinister now to those culture warriors who think organisations and the HR profession are pushing ‘woke ideology’.)

Culture’s inherent intangibility can mean a tendency to focus on if not the wrong, then certainly the most superficial, things. With culture perhaps too abstract to be practical, it is tempting to drift towards interventions that simply are not that meaningful. “Many leaders will go for the things they feel are tangible: value statements, big events, buying water bottles with the purpose on them,” Spicer says. “Those things don’t change culture. Culture is changed through day-to-day interactions and rituals, which are hard levers to pull.”

Indeed, evidence-based HR evangelist Rob Briner, professor of organisational psychology at Queen Mary University of London, believes carelessness in the business community over what we mean when we talk about culture is damaging, turning an important concept into a “thought-terminating cliché”. “People bring it out when they are trying to explain or change something that they can’t explain or change, so they say it’s culture,” he explains. “It sounds like you’re doing something or have understood something, but typically you haven’t at all.”

For Briner, the nebulous nature of the construct means business leaders would be far better off talking about what they actually mean, which is normally behaviours. Branding specific people challenges ‘culture’, he feels, is merely “kicking the can down the road” instead of taking meaningful action. “Throwing around ‘culture’ is dangerous as it distracts you from getting underneath what is going on or what you want to change,” he adds. He uses the Met Police’s ongoing review as an example: “Is it the culture, or is it a terrible selection process?” (Of course, proponents of culture would argue that the two are inextricably linked.)

Briner’s dismissal of the concept may be a little provocative, but many advocates of workplace culture as a critical area of HR and leadership practice would still agree that companies often do not address it in the best way, relying on surface-level interventions and not always having the appetite to get into the really hard stuff. “We tend to be interested in the bright shiny side of culture, rather than the dark side,” says Susan Hetrick, organisational psychologist, consultant and expert on toxic cultures. Hetrick has observed culture becoming more and more important to businesses over her career and believes the financial crisis and resulting FCA report (which claimed failures of culture in the banking sector cost the UK economy hundreds of billions) was an inflection point, with leaders starting to recognise culture as a driver of financial performance. But she questions whether every leader is “putting their money where their mouth is’’, or focusing too much on values and purpose statements at the expense of sustained behavioural and operational change. Reflecting this, the Financial Reporting Council’s 2020 review of Corporate Governance Code compliance criticised many firms for providing little more than “a marketing slogan”, with only 52 per cent commenting on their culture “in a meaningful way”.

Substantial, worthwhile commentary is always going to be challenging if cultural interventions are only scratching the surface – but does ‘the way we do things around here’ really have an impact on organisational performance? Spicer says there is plenty of evidence linking culture to competitiveness or lack thereof. “There are particular cultures that might drive particular performance, and different kinds of culture might matter more in different industries,” he adds. In higher-touch, service-focused industries, having a more humanistic culture may be more important than within a systems-focused sector.

Indeed, Peter Cheese, CEO of the CIPD, points out that many organisations have sub-cultures in different units, functions, geographies, even teams – which isn’t necessarily a problem. “When we talk about culture, we need to talk about what is material,” he says. “Is it really culture that is making the difference to that organisation’s performance?” Musing on ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’, Cheese posits that Drucker was referring to the way culture can get in the way of success, with the quote in fact describing a culture of “passive resistance”, whereby strategic change is not possible because people are anxious, uncertain or not on board: “I think he was referring to those barriers, the ways in which culture holds you back.”

Even more dangerous than passive resistance is an actively toxic culture, whereby bad behaviour causes serious harm to individuals and organisations. There is no shortage of timely examples – the Post Office scandal, Boeing’s safety issues, a lack of psychological safety within parts of the NHS – all of which have cost lives. “Every corporate culture will have some element of toxicity,” warns Hetrick. “If not contained, that will spill into the rest of the organisation.” With lives at risk, the stakes could not be higher. So how can HR shape a positive culture? While Briner remains sceptical of ‘culture’ as a catch-all descriptor, he has a few suggestions: “If you want to change behaviours, you have to first understand what behaviours you want in the business, the behaviours you’ve got and then the most appropriate interventions. That might involve selection, training, job design, getting rid of a lot of senior managers…”

HR should examine processes to see if they undermine the desired culture and values, Hetrick adds. “You could have collaboration as a value and it be undermined by performance management that is focused on the individual.” Cheese agrees: “One of the strongest HR levers is what you are holding people to account for, and how that affects their performance, reward and progression.” So, it is taking those more tangible elements of HR practice and thinking about them systematically (what could be causing unintended behavioural consequences?) that makes a difference, whether you call it culture or not.

Creating artworks by culturing micro-organisms – bacteria, yeast, fungi or protists – is a bit like painting. But because the hues are living cells, it is hard to control exactly what they will do – much like organisational culture, you might say. For artists trying to configure very specific images (astronauts, goldfish, Vincent van Gogh…) this can be irksome. For others – as with these shortlisted entries to last year’s Agar Art Contest – there is a delicate balance between nudging the microbes and allowing unexpected, beautiful abstractions to unfold | Day of Science, 2023 Agar Art © American Society for Microbiology

Creating artworks by culturing micro-organisms – bacteria, yeast, fungi or protists – is a bit like painting. But because the hues are living cells, it is hard to control exactly what they will do – much like organisational culture, you might say. For artists trying to configure very specific images (astronauts, goldfish, Vincent van Gogh…) this can be irksome. For others – as with these shortlisted entries to last year’s Agar Art Contest – there is a delicate balance between nudging the microbes and allowing unexpected, beautiful abstractions to unfold | Day of Science, 2023 Agar Art © American Society for Microbiology

To ascertain whether culture really eats strategy for breakfast (as management guru Peter Drucker had it), it is first worth diving into its history. While Schein is one of the most influential early names in organisational culture, it was Canadian psychoanalyst and social scientist Elliott Jacques who came up with the commonly used definition of culture as ‘the way we do things around here’, extending culture beyond its more traditional anthropological meaning. Jacques (who also coined the term ‘midlife crisis’) observed the culture within a London ball-bearing factory over three years, publishing The Changing Culture of a Factory in 1951.

But it was not until the 1980s that culture became seen as something for business leaders to pay attention to and attempt to manipulate, says André Spicer, professor of organisational behaviour at Bayes Business School. “Companies had been trying to change culture for years, but an explicit focus on corporate culture came out of the 1980s, largely driven by the ‘Japanese threat’,” he explains. That led to an obsession with replicating corporate Japan’s ‘quality’ culture, which then morphed into a focus on innovation during the late 1990s’ dotcom bubble. The global financial crisis brought sharp attention to the damaging impact of high-risk and unethical cultures – “getting the culture right to stop people doing wrong things”, as Spicer puts it. And it led to the introduction of more oversight and regulation. Today, discussion is often tied to the post-pandemic return to the office, with concern over the impact of long-term remote working on corporate culture.

What still remains somewhat woolly is how we define culture – everyone might be talking about it, but the chances are we are all talking about slightly different things. As a CIPD paper exploring the difference between culture and climate reads: “The problem with the concept of organisational culture is not that it lacks meaning, but that it has too many meanings.” In fact there are more than 50 distinct definitions in academic literature. Ask a business or HR leader and it is likely they will quote Jacques. But Spicer rates Schein’s description of culture as ‘an iceberg’ – with visible artefacts at the top and harder to define or understand values and assumptions lying beneath the water’s surface – as the best. (Schein also proposed that organisational culture is passed on or taught to people as “the correct way to perceive, think and feel”, something that could sound rather sinister now to those culture warriors who think organisations and the HR profession are pushing ‘woke ideology’.)

Culture’s inherent intangibility can mean a tendency to focus on if not the wrong, then certainly the most superficial, things. With culture perhaps too abstract to be practical, it is tempting to drift towards interventions that simply are not that meaningful. “Many leaders will go for the things they feel are tangible: value statements, big events, buying water bottles with the purpose on them,” Spicer says. “Those things don’t change culture. Culture is changed through day-to-day interactions and rituals, which are hard levers to pull.”

Indeed, evidence-based HR evangelist Rob Briner, professor of organisational psychology at Queen Mary University of London, believes carelessness in the business community over what we mean when we talk about culture is damaging, turning an important concept into a “thought-terminating cliché”. “People bring it out when they are trying to explain or change something that they can’t explain or change, so they say it’s culture,” he explains. “It sounds like you’re doing something or have understood something, but typically you haven’t at all.”

For Briner, the nebulous nature of the construct means business leaders would be far better off talking about what they actually mean, which is normally behaviours. Branding specific people challenges ‘culture’, he feels, is merely “kicking the can down the road” instead of taking meaningful action. “Throwing around ‘culture’ is dangerous as it distracts you from getting underneath what is going on or what you want to change,” he adds. He uses the Met Police’s ongoing review as an example: “Is it the culture, or is it a terrible selection process?” (Of course, proponents of culture would argue that the two are inextricably linked.)

Briner’s dismissal of the concept may be a little provocative, but many advocates of workplace culture as a critical area of HR and leadership practice would still agree that companies often do not address it in the best way, relying on surface-level interventions and not always having the appetite to get into the really hard stuff. “We tend to be interested in the bright shiny side of culture, rather than the dark side,” says Susan Hetrick, organisational psychologist, consultant and expert on toxic cultures. Hetrick has observed culture becoming more and more important to businesses over her career and believes the financial crisis and resulting FCA report (which claimed failures of culture in the banking sector cost the UK economy hundreds of billions) was an inflection point, with leaders starting to recognise culture as a driver of financial performance. But she questions whether every leader is “putting their money where their mouth is’’, or focusing too much on values and purpose statements at the expense of sustained behavioural and operational change. Reflecting this, the Financial Reporting Council’s 2020 review of Corporate Governance Code compliance criticised many firms for providing little more than “a marketing slogan”, with only 52 per cent commenting on their culture “in a meaningful way”.

Substantial, worthwhile commentary is always going to be challenging if cultural interventions are only scratching the surface – but does ‘the way we do things around here’ really have an impact on organisational performance? Spicer says there is plenty of evidence linking culture to competitiveness or lack thereof. “There are particular cultures that might drive particular performance, and different kinds of culture might matter more in different industries,” he adds. In higher-touch, service-focused industries, having a more humanistic culture may be more important than within a systems-focused sector.

Indeed, Peter Cheese, CEO of the CIPD, points out that many organisations have sub-cultures in different units, functions, geographies, even teams – which isn’t necessarily a problem. “When we talk about culture, we need to talk about what is material,” he says. “Is it really culture that is making the difference to that organisation’s performance?” Musing on ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’, Cheese posits that Drucker was referring to the way culture can get in the way of success, with the quote in fact describing a culture of “passive resistance”, whereby strategic change is not possible because people are anxious, uncertain or not on board: “I think he was referring to those barriers, the ways in which culture holds you back.”

Even more dangerous than passive resistance is an actively toxic culture, whereby bad behaviour causes serious harm to individuals and organisations. There is no shortage of timely examples – the Post Office scandal, Boeing’s safety issues, a lack of psychological safety within parts of the NHS – all of which have cost lives. “Every corporate culture will have some element of toxicity,” warns Hetrick. “If not contained, that will spill into the rest of the organisation.” With lives at risk, the stakes could not be higher. So how can HR shape a positive culture? While Briner remains sceptical of ‘culture’ as a catch-all descriptor, he has a few suggestions: “If you want to change behaviours, you have to first understand what behaviours you want in the business, the behaviours you’ve got and then the most appropriate interventions. That might involve selection, training, job design, getting rid of a lot of senior managers…”

HR should examine processes to see if they undermine the desired culture and values, Hetrick adds. “You could have collaboration as a value and it be undermined by performance management that is focused on the individual.” Cheese agrees: “One of the strongest HR levers is what you are holding people to account for, and how that affects their performance, reward and progression.” So, it is taking those more tangible elements of HR practice and thinking about them systematically (what could be causing unintended behavioural consequences?) that makes a difference, whether you call it culture or not.

Outer space by artist Nisanur Meral © American Society for Microbiology

Outer space by artist Nisanur Meral © American Society for Microbiology

If you are an HR or business leader looking to shape or change culture, you will find no shortage of experts willing to help you. The culture industry is thriving, with everyone from the largest consultancies to smallest ‘one man bands’ ready and willing to come and ‘fix’ your culture – for a price. While getting external input can be invaluable and the best consultants are clear they are not selling an overnight solution, is the increasing commodification of culture a cause for concern? Richard Cotter, head of organisational development and research at insurance firm Allianz Ireland, fears it might be. “The culture industry promises so much but delivers so little,” he says. “I have nothing against consultants, but when culture becomes a product, does that pathologise it? Too many people accept definitions of culture from the outside – and methods – without critically thinking about them. Business is always looking for the next big thing, but the one thing people never seem able to pin down is culture. It’s thrown around as the reason for things being good or bad.”

But that does not mean Cotter is a culture sceptic – far from it. Rather, he has taken a slightly more left-field approach, embedding a ‘business anthropologist’ in the organisation. Having explored anthropological techniques during his PhD, Cotter was convinced this would bring more value than the ubiquitous surveys and dashboards. It might sound esoteric, but historically culture is grounded after all in anthropology, the study of how humans interact. And what is an organisation made up of if not thousands of everyday interactions? Cotter believes taking this group dynamic approach, focusing on shifting the environments in which people interact, is more impactful and sensible than a psychological approach that attempts to change individual mindsets. “The mind is a mysterious thing, so why do we believe we can change people’s mindsets?” he asks. “You could even argue it’s not our business to do so. It’s better to improve the situations people interact in.”

In practice, having an anthropologist on site means deploying them to observe people, taking ‘field notes’ on everything from what they say to where they sit and their body language. These lead to recommendations on how to make interactions more positive and productive, including changing seating arrangements, office design and the frequency and flow of meetings. Cotter believes he can draw a clear line between this approach and better business outcomes, thanks in part to improved collaboration. And he is far from alone, with the idea of anthropology relating to corporate culture – though still unusual in HR circles – slowly working its way into the mainstream, via the work, for example, of Financial Times journalist and anthropologist Gillian Tett. The key, Cotter adds, has been figuring out “tangible, pragmatic” ways to work on culture, while accepting that some elements of how people relate to each other at work will always be hard to understand. To quote Tett: “Trying to define culture is just as frustrating as trying to chase soap in the bath – but we can’t ignore it.”

Cotter’s is an intriguing and scientific approach, but Cheese warns against HR professionals getting “too esoteric”, especially when talking to business leaders. Cotter’s leadership team has been nothing but receptive, but not all would be so open minded. “Many leaders just want us to show them what we can practically do that’s material to business,” Cheese says, agreeing that trying to understand and measure every dimension of culture is a hiding to nothing.

According to a 2023 CIPD report, one way of getting closer to understanding what we mean by culture and how to change it is to switch focus to the more specific ‘climate’. Organisational climate is defined as “the shared perceptions of and the meaning attached to the policies, practices and procedures employees experience”. It is clearly linked to behaviours, focuses on specific dimensions (safety climate, innovation climate, ethical climate, inclusion climate and so on) and can be more accurately assessed owing to a more concrete evidence base.

Briner says climate makes sense to him as “a sounder kind of construct”. But there is still undoubtedly a risk of turning leaders off. Accurate language may be important, but even the CIPD report acknowledges the case for framing insights in terms of culture if that is what stakeholders respond to. Culture may be ill-defined and tricky to get a handle on, but many leaders still feel they instinctively understand it. The job of HR professionals is to pull the right levers to make necessary and meaningful changes, which is where an understanding of climate could help.

So, culture is nebulous, slippery and, to many leaders, more important than ever. How much does it really count? “It matters – often more than we think it does,” Spicer concludes. But, he adds: “Often the ways we make interventions around culture matter far less than we think they do.” It is spending too much time on those ineffective, even damaging, interventions that is more problematic than spending time trying to grasp an abstract concept. Nothing in an organisation exists in isolation and taking a whole systems approach to any people practice is the best defence against negative unintended consequences. Culture might not quite eat strategy for breakfast, particularly if we are not focusing on the right things. But without an appreciation of the influence and impact of group dynamics (whatever we choose to call that), strategy might not even make it out of bed in the morning.

Top left: Contrast by llknur Emir © American Society for Microbiology; top right: Day of Science © American Society for Microbiology; bottom left: A Blue Planet by Daiki Tanno © American Society for Microbiology; bottom right: Sea Jelly © American Society for Microbiology

Top left: Contrast by llknur Emir © American Society for Microbiology; top right: Day of Science © American Society for Microbiology; bottom left: A Blue Planet by Daiki Tanno © American Society for Microbiology; bottom right: Sea Jelly © American Society for Microbiology

Top left: Contrast by llknur Emir © American Society for Microbiology; top right: Day of Science © American Society for Microbiology; bottom left: A Blue Planet by Daiki Tanno © American Society for Microbiology; bottom right: Sea Jelly © American Society for Microbiology

Top left: Contrast by llknur Emir © American Society for Microbiology; top right: Day of Science © American Society for Microbiology; bottom left: A Blue Planet by Daiki Tanno © American Society for Microbiology; bottom right: Sea Jelly © American Society for Microbiology

If you are an HR or business leader looking to shape or change culture, you will find no shortage of experts willing to help you. The culture industry is thriving, with everyone from the largest consultancies to smallest ‘one man bands’ ready and willing to come and ‘fix’ your culture – for a price. While getting external input can be invaluable and the best consultants are clear they are not selling an overnight solution, is the increasing commodification of culture a cause for concern? Richard Cotter, head of organisational development and research at insurance firm Allianz Ireland, fears it might be. “The culture industry promises so much but delivers so little,” he says. “I have nothing against consultants, but when culture becomes a product, does that pathologise it? Too many people accept definitions of culture from the outside – and methods – without critically thinking about them. Business is always looking for the next big thing, but the one thing people never seem able to pin down is culture. It’s thrown around as the reason for things being good or bad.”

But that does not mean Cotter is a culture sceptic – far from it. Rather, he has taken a slightly more left-field approach, embedding a ‘business anthropologist’ in the organisation. Having explored anthropological techniques during his PhD, Cotter was convinced this would bring more value than the ubiquitous surveys and dashboards. It might sound esoteric, but historically culture is grounded after all in anthropology, the study of how humans interact. And what is an organisation made up of if not thousands of everyday interactions? Cotter believes taking this group dynamic approach, focusing on shifting the environments in which people interact, is more impactful and sensible than a psychological approach that attempts to change individual mindsets. “The mind is a mysterious thing, so why do we believe we can change people’s mindsets?” he asks. “You could even argue it’s not our business to do so. It’s better to improve the situations people interact in.”

In practice, having an anthropologist on site means deploying them to observe people, taking ‘field notes’ on everything from what they say to where they sit and their body language. These lead to recommendations on how to make interactions more positive and productive, including changing seating arrangements, office design and the frequency and flow of meetings. Cotter believes he can draw a clear line between this approach and better business outcomes, thanks in part to improved collaboration. And he is far from alone, with the idea of anthropology relating to corporate culture – though still unusual in HR circles – slowly working its way into the mainstream, via the work, for example, of Financial Times journalist and anthropologist Gillian Tett. The key, Cotter adds, has been figuring out “tangible, pragmatic” ways to work on culture, while accepting that some elements of how people relate to each other at work will always be hard to understand. To quote Tett: “Trying to define culture is just as frustrating as trying to chase soap in the bath – but we can’t ignore it.”

Cotter’s is an intriguing and scientific approach, but Cheese warns against HR professionals getting “too esoteric”, especially when talking to business leaders. Cotter’s leadership team has been nothing but receptive, but not all would be so open minded. “Many leaders just want us to show them what we can practically do that’s material to business,” Cheese says, agreeing that trying to understand and measure every dimension of culture is a hiding to nothing.

According to a 2023 CIPD report, one way of getting closer to understanding what we mean by culture and how to change it is to switch focus to the more specific ‘climate’. Organisational climate is defined as “the shared perceptions of and the meaning attached to the policies, practices and procedures employees experience”. It is clearly linked to behaviours, focuses on specific dimensions (safety climate, innovation climate, ethical climate, inclusion climate and so on) and can be more accurately assessed owing to a more concrete evidence base.

Briner says climate makes sense to him as “a sounder kind of construct”. But there is still undoubtedly a risk of turning leaders off. Accurate language may be important, but even the CIPD report acknowledges the case for framing insights in terms of culture if that is what stakeholders respond to. Culture may be ill-defined and tricky to get a handle on, but many leaders still feel they instinctively understand it. The job of HR professionals is to pull the right levers to make necessary and meaningful changes, which is where an understanding of climate could help.

So, culture is nebulous, slippery and, to many leaders, more important than ever. How much does it really count? “It matters – often more than we think it does,” Spicer concludes. But, he adds: “Often the ways we make interventions around culture matter far less than we think they do.” It is spending too much time on those ineffective, even damaging, interventions that is more problematic than spending time trying to grasp an abstract concept. Nothing in an organisation exists in isolation and taking a whole systems approach to any people practice is the best defence against negative unintended consequences. Culture might not quite eat strategy for breakfast, particularly if we are not focusing on the right things. But without an appreciation of the influence and impact of group dynamics (whatever we choose to call that), strategy might not even make it out of bed in the morning.

Editor Jenny Roper

Art director Aubrey Smith

Freelance art editor Kayleigh Pavelin

Production editor Joanna Matthews

Picture editor Dominique Campbell

Editor in chief Robert Jeffery

Image credits

Nnorozoff/iStock/Getty Images; © American Society for Microbiology,